Near the end of The Caine Mutiny (1954) there's a startling close-up of Van Johnson in which his pronounced facial scars from a 1943 car accident, so carefully hidden by studio makeup artists for so many years, are revealed more fully than they'd ever been on screen.

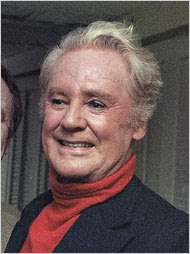

Johnson’s role isn’t major in The Caine Mutiny but the project was among the most prestigious he landed during the postwar era. It came a little more than a decade after the eternally boyish actor with the ginger-colored hair and ultrafair complexion—he used to crack that he got paid by the freckle—rose to screen fame during wartime. The bobby-soxers screamed over him. He could dance very well and sing well enough, as evidenced by this duet with Lucille Bremer from Till the Clouds Roll By (1946):

Nonetheless Johnson became known as “the voiceless Sinatra.” And thanks to films such as A Guy Named Joe and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo he became huge.

But by the time of The Caine Mutiny when his star had fallen, getting out from underneath his usual scar-concealing makeup may well have been a relief.

Johnson died in 2008 at 92, and most of the obituaries ignored the part of his life spent largely behind another kind of facade. Some stories alluded to a “difficult” marriage. There’s enough on the record by now that we do a disservice to Johnson, and to the studio system that built his image, if we leave it at that.

Like Rock Hudson, Johnson—according to his ex-wife—was pressured by studio bosses into a marriage tailored to the image maintenance of a well-liked movie star. Hours after divorcing character actor Keenan Wynn, an old friend and fellow MGM contract player of Johnson’s, Evie Wynn married Johnson in 1947. They had one daughter. They separated around the time Johnson, according to The Independent newspaper of London, among other sources, had an affair with a male dancer in the London company of “The Music Man,” which starred Johnson as Professor Harold Hill. Johnson and Wynn Johnson divorced in 1968.

In 1999, five years before her death, Johnson’s ex-wife wrote of MGM: “They needed their ‘big star’ to be married to quell rumours about his sexual preferences.” She characterized MGM chief Louis B. Mayer as someone with “the ethics and morals of a cockroach,” and said Mayer put it to her plainly: “Unless I married Van Johnson, he wouldn’t renew Keenan’s contract. I was young and stupid enough to let Mayer manipulate me.”

After appearing on Broadway in the musicals “Too Many Girls” and, with Gene Kelly, “Pal Joey,” Johnson found stardom quickly and easily, though he did not find it easy. The MGM starmaking machinery was intense, and Johnson later acknowledged that he wasn’t ready for the publicity glare. In the biography “Van Johnson: MGM’s Golden Boy,” author Ronald L. Davis (who characterized Johnson’s orientation as “more homosexual than heterosexual”) notes Johnson, like other heartthrobs of the day, was “often pictured in the fan magazines with a rifle or an ax in his hand or engaged in some form of home repair.” Around that time Johnson told one interviewer: “I’m married to MGM. I have one love and it’s pictures.”

Johnson’s passing was one of those “was he still alive?” moments for many film fans. He was easy to take for granted. Yet when you examine this man’s utilitarian versatility, his slightly arch personification of the galoot-next-door, his career is worth a second look.

That near-fatal 1943 car accident kept him out of the war, and with so many other leading male stars off doing their bit for Uncle Sam, Johnson was pressed into onscreen service for hit after hit. Then his luck slowly waned. He made a mistake by turning down the lead in the TV series “The Untouchables,” which went instead to Robert Stack. Johnson kept busy, though, in films and TV, in nightclubs, and in scads and scads of dinner-theater productions. (I remember seeing a 1980s publicity photo taken for Casa Manana Theatre of Ft. Worth, with Johnson mugging up a storm as Moonface Martin in “Anything Goes.”)

Around the same time he turned up in a cameo in Woody Allen’s “Purple Rose of Cairo.” And on Broadway, also in the 1980s, Johnson at long last played a gay man comfortable in his sexuality, adept at song and dance, full of life, in “La Cage aux Folles,” by which time the voiceless Sinatra was no longer worried about what MGM or the bobby-soxers or anyone else thought about his image...

SOURCE

Every time I watch the Caine Mutiny over the years I find myself being increasingly drawn to Johnson's character's conflict. His was an outstanding and under-rated performance.

ReplyDeleteVan Johnson was good, Humphrey Bogart was great. Lee Marvin was interesting, Jose Ferrar riveting. Great movie. Seeing, Bogart play a disturbed,weak Captain was seeing a great actor perform.

DeleteWHY IS HIS PREFERENCE OF SEX ALWAYS INCLUDED? I HAVE 3 SITES I PUT PHOTOS OF HIM ON AND ABOUT THE TIME I FIND A WRITING OF HIM I CANNOT PUT IT ON CAUSE THE SEX LIFE IS MENTIONED. I WANT YOU TO KNOW HE LIKED WOMEN TOO.

ReplyDelete.