Friday, April 29, 2011

TCM FESTIVAL RETURNS

TCM Classic Film Festival Returns to Hollywood

By Rebecca Ford

The TCM Classic Film Festival returns to Hollywood beginning Thursday for four days of classic films, celebrity appearances, guest speakers and panel discussions.

Most film festivals try to introduce new and upcoming films to the world, but the TCM festival showcases classic films with more than 70 screenings through May 1.

The main goal of the festival is “to further build a community for classic film lovers, create a place where they can gather, celebrate their shared passion and immerse themselves in a classic movie environment,” said Charlie Tabesh, senior vice president of programming at TCM and head programmer of the festival.

Now in its second year, the film festival will hold screenings at several Hollywood locations, including Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, the Egyptian Theatre and poolside at The Roosevelt Hotel. Club TCM, a gathering spot for mingling and special guest speakers, will be located in the Blossom Room at the historic Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, the site of the first Academy Awards ceremony.

Tabesh is especially excited for Buster Keaton's The Cameraman with live accompaniment by Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks orchestra. Other programming highlights include the world premiere of the 60th anniversary restoration of An American in Paris, a screening of Shall We Dance with Alexis Gershwin (niece of George and Ira Gershwin), Citizen Kane, A Streetcar Named Desire, Taxi Driver, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Shaft, Girl Happy, Goldfinger, To Kill a Mockingbird, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and West Side Story.

Kirk Douglas will join TCM host Robert Osborne for an interview on stage, leading into a screening of Stanley Kubrick’s film Spartacus on the second day of the festival. Peter O’Toole, Kirk Douglas, Warren Beatty, Leslie Caron, Roger Corman, Mariel Hemingway, Angela Lansbury, Jerry Mathers, Hayley Mills, Jane Powell, Debbie Reynolds, Mickey Rooney, Richard Roundtree, Barbara Rush and Alec Baldwin are some of the celebrities slated to appear during the festival.

“I think this year there is much more a sense of anticipation since we did it once successfully, so I hope we can surpass what we did last year,” Tabesh said.

SOURCE

Thursday, April 28, 2011

BORN ON THIS DAY: LIONEL BARRYMORE

During World War I Lionel staved off the deadly Spanish Influenza by taking cold alcohol baths as an antiseptic.He was married twice, to actresses Doris Rankin and Irene Fenwick, a one-time lover of his brother John. Doris's sister Gladys was married to Lionel's uncle Sidney Drew, which made Gladys both his aunt and sister-in-law.

Doris Rankin bore Lionel two daughters, Ethel Barrymore II (b. 1908) and Mary Barrymore. Unfortunately, neither baby girl survived infancy, though Mary lived a few months. Lionel never truly recovered from the deaths of his girls, and their loss undoubtedly strained his marriage to Doris Rankin, which ended in 1923. Years later, Barrymore developed a fatherly affection for Jean Harlow, who was born about the same time as his two daughters and would have been about their age. When Jean died in 1937, Lionel and Clark Gable mourned her as though she had been family.

In 1924, he left Broadway for Hollywood. He starred as Frederick Harmon in director Henri Diamant-Berger's drama Fifty-Fifty (1925) opposite Hope Hampton and Louise Glaum, and made several other freelance motion pictures, including The Bells (Tiffany Pictures 1926) with a then-unknown Boris Karloff. After 1926, however, he worked almost exclusively for MGM, appearing opposite such luminaries as John Gilbert, Lon Chaney, Sr., Jean Harlow, Wallace Beery, Marie Dressler, Greta Garbo, and his brother John.

On the occasional loan-out, Barrymore had a big success with Gloria Swanson in 1928's Sadie Thompson and the aforementioned Griffith film, Drums of Love. Talkies were now a reality and Barrymore's stage-trained voice recorded well in sound tests. In 1929, he returned to directing films. During this early and imperfect sound film period, he made the controversial His Glorious Night with John Gilbert, Madame X starring Ruth Chatterton, and Rogue Song, Laurel & Hardy's first color film. Barrymore returned to acting in front of the camera in 1931.

In that year, he won an Academy Award for his role as an alcoholic lawyer in A Free Soul (1931), after being nominated in 1930 for Best Director for Madame X. He could play many characters, like the evil Rasputin in the 1932 Rasputin and the Empress (in which he co-starred with siblings John and Ethel) and the ailing Oliver Jordan in Dinner at Eight (1933 - also with John Barrymore, although they had no scenes together).

In a series of Doctor Kildare movies in the 1930s and 1940s, he played the irascible Doctor Gillespie, repeating the role he'd created in the radio series throughout the 1940s. He also played the title role in another 1940s radio series, Mayor of the Town. Barrymore had broken his hip in an accident, hence he played Gillespie in a wheelchair; later, his worsening arthritis kept him in the chair. The injury also precluded his playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 MGM film version of A Christmas Carol, a role Barrymore played every year but one on the radio from 1934 through 1953.

Perhaps his best known role, thanks to perennial Christmastime replays on television, was Mr. Potter, the miserly and mean-spirited banker in It's a Wonderful Life (1946). His final film appearance was a cameo in Main Street to Broadway, an MGM musical comedy released in 1953. His sister Ethel also appeared in the film.

Lionel Barrymore died on November 15, 1954 from a heart attack in Van Nuys, California, and was entombed in the Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles, California...

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

HAL LINDEN AT 80

Hal Linden To Release Debut CD

Los Angeles, CA (PRWEB) April 22, 2011

Hal Linden, the Emmy and Tony Award-winning actor, who became a household name with his portrayal of police precinct captain Barney Miller in the hit television series, realizes a lifelong dream this Tuesday, April 26, with the release of his first CD, It’s Never Too Late.

The disc is a diverse collection of Broadway and feature film tunes, classic pop songs, as well as jazz standards and favorites from the American Songbook that Linden recorded over a period of three decades in a variety of settings—large and small studios, with big bands and combos, in locations from New York to Los Angeles.

Linden, an accomplished singer and musician, (he’s a classically trained clarinetist), worked with several top arrangers to put his own stamp on well-known tunes such as Cole Porter’s “You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To,” which opens the 14-track album. It’s followed by a medley of “Mississippi Mud,” first recorded in 1928 and made popular by Bing Crosby, and the Hoagy Carmichael song “Up A Lazy River.”

The disc shifts gears with a soulful version of “She’s Out of My Life,” arranged by renowned jazz pianist and Grammy-award winner Bob Florence, who has worked with Harry James, Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson and Doc Severinson. Florence also arranged “If I Could,” a hit for Regina Belle and, later, a staple of Celine Dion’s Las Vegas show.

Linden worked on Broadway for many years, so it is only fitting that tunes from the Great White Way find a home here, including “Hello Dolly!,” which features additional lyrics penned by songwriter Jerry Herman, and Stephen Sondheim’s Zigfield-esque “Beautiful Girls” from his 1971 musical Follies.

Film music is well represented on It’s Never Too Late including the Grammy, Golden Globe and Academy Award-winning hits “You Light Up My Life,” and “Evergreen.” Linden gives the former a new twist, by adding a gospel choir. A touch of pedal steel on “Moon River,” gives the classic country colors. (Interesting trivia: It was Linden who performed “You Light Up My Life” at the Golden Globes ceremony in 1978, where it won the award for Best Original Song, and later tied for Song Of The Year with “The Love Theme From A Star Is Born (Evergreen)” at the Grammy Awards).

Other cuts include Billy Joel’s “She’s Got a Way,” that Linden delivers with a jazzy edge, a perfect complement to the artist’s own tune “Meet Me At Jack’s,” a cool, finger-snappin’ number originally written as the potential theme song for the television series Jack’s Place. Linden plays clarinet on several tracks including the instrumental “There Will Never Be Another You.” The CD closes with “Late In Life,” a track that holds particular meaning for Linden, with the lyric “It’s never too late in life to reach for a childhood dream.”

Linden, who came of age during the Big Band era, had indeed dreamed of leading a band of his own, where he could sing, play the clarinet, tour and make records. When he returned from a stint in the army, however, he realized that big bands were less in demand and his career path subsequently led him to the stage, film and television. Linden celebrated his 80th birthday in March, while on tour with his successful cabaret-style act, An Evening With Hal Linden, that has earned him rave reviews. “Hal Linden wows them,” notes the Portland Oregonian, “…a triple-threat performer with a big voice.”

With the new CD, Linden proves it's never too late to reach for our dreams.

SOURCE

Monday, April 25, 2011

RIP: CELIA LIPTON

Celia Lipton, who died on March 11 aged 87, was a child star, known as the “British Judy Garland”, who went on to become a Forces sweetheart in the Second World War; later she gave up a successful stage career to marry the American inventor and industrialist Victor Farris and became the acknowledged 'Queen of Palm Beach society’.

Like any society hostess and former actress Celia Lipton was always vague about her age and was furious when a magazine obtained a copy of her birth certificate, showing that Celia May Lipton was born on Christmas Day 1923, at 73 Leamington Terrace, Edinburgh. Her father was an English violinist, Sidney John Lipton — as Sydney Lipton he would become one of Britain’s top bandleaders; her mother was May Johnston Parker, a dancer, singer and noted Scottish beauty.

When Celia was eight, her father formed his own band and took it to the Grosvenor House Hotel in Park Lane, where he was to remain for 35 years. Enthralled by watching the singers and chorus girls at the hotel putting on their make-up and diamonds to go on stage, Celia determined to go into showbusiness. Her chance came when, aged about 10, she spotted an advertisement asking for a Judy Garland sound-alike to play the lead in a BBC radio production of Babes In the Wood. Determined to get the part, she perfected Garland’s lisp and breathy singing style. When her parents refused to let her audition, she set off on her own and secured the part.

When the Second World War broke out, her father joined up as a private and was away from the family for seven years. As a result Celia became the family breadwinner. She sang to 2,000 troops at the Albert Hall, to severely disfigured men at the burns unit in East Grinstead, to the forces on the European front and at RAF hangars across the country, becoming known for Maybe It’s Because I’m A Londoner and You’ve Got Your Own Life To Live. With her mother as chaperone she toured Britain.

Her greatest triumphs, though, were her appearances as Peter Pan at the Scala Theatre, Tottenham Court Road, in 1943 and 1944 (the “best ever seen in a London theatre” according to one critic), and in Lionel Monckton’s 1944 revival of the light opera, The Quaker Girl, when she stepped in for Jessie Matthews at the last moment and received a dozen curtain calls on opening night at the Coliseum.

After the war Celia Lipton travelled to Paris and then the French Riviera where, on one occasion, she met the young Prince Philip of Greece, who offered to escort her to the casino in Cannes. “I asked him how we were going to get there and he said he’d borrowed a man’s bike and he put me on the back of it,” she recalled in 2004. “My dress kept catching in the back of the bike. I was lucky since I got to dance with him. He was an exceptionally good dancer.”

She also launched herself on a film career. After making her debut supporting John Bentley and Dinah Sheridan in Calling Paul Temple (1948), she appeared opposite Sonia Dresdel and Walter Fitzgerald in the adaptation of Joan Morgan’s novel, This Was A Woman (1948) and played Sandra in Terrence Young’s melodrama The Frightened Bride (1952).

In 1952 Celia Lipton moved to New York, where she joined the all-star revue, John Murray Anderson’s Almanac (1953-54) at the Imperial Theatre, Broadway, and appeared as Esmeralda to Robert Ellenstein’s Quasimodo in a television version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1954).

While in New York, she met Victor Farris. “I was returning some books to a friend and there was a man up on a ladder fixing a fan – my future husband,” she recalled. At first she thought he was a plumber and then, maybe, a member of the Mafia. In fact he owned 17 companies, was the inventor of the paper milk carton, the paper clip and the Farris Safety and Relief Valve, still used in shipping, oil and chemical industries. He was also a millionaire many times over. The couple wed in 1956, with Celia giving up showbusiness to devote herself to married life in New Jersey and, later, Florida.

Although the marriage was not without its difficulties — her relationship with her husband was sometimes volatile and Celia suffered ten miscarriages and gave birth prematurely to two babies who both died within a week — it was a happy one. At their sumptuous mansion in Palm Beach, once owned by the Vanderbilts, Celia became a leading society hostess.

When Victor Farris died of a heart attack in 1985, closely followed by her parents, Celia’s life altered dramatically again. Her husband had left her his £100 million fortune (an amount she more than doubled through shrewd investments over subsequent years), and she embarked on a new phase of her life as a philanthropist and charity fundraiser. “There are a lot of silly, socially competitive, frivolous women in this town who gossip, go out to lunch every day and dinner every night and that’s it,” she observed. “I’m delighted that I know what hard work is and proud of my Scottish mother and the good Scottish common sense she taught me.”

A convert to Catholicism, she raised large sums for the Salvation Army, the American Heart Association and cancer research charities. At a time when the disease was taboo she was one of the first big private benefactors of Aids research. Other beneficiaries included the National Trust for Scotland, the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital, the American Red Cross, the Prince’s Trust and the Duke of Edinburgh Trust.

In addition she became Executive Producer of the American Cinema Awards in Hollywood (which raises funds for actors who have fallen on hard times); sang before the Queen at the 50th anniversary of VE Day in Hyde Park, made a brief screen comeback with Burt Reynolds in BL Stryker (1989-1990), and released a series of her own, self-financed, CDs. In 2008, she published her autobiography My Three Lives.

In her autobiography Celia Lipton related that she was “honoured to receive a letter informing me that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth had appointed me a Dame”, conveying the impression that she had been created DBE. In fact, in 2004 she was named a Dame of Grace of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, entitling her to place the letters D St J after her name. Nonetheless she headed her personal notepaper, Dame Celia Lipton Farris, and, in America, was announced by that style on social occasions.

She is survived by two adopted daughters.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

MOVIE SHOWCASE: THE LIFE OF BRIAN

The film contains themes of religious satire which were controversial at the time of its release, drawing accusations of blasphemy and protests from some religious groups. Thirty-nine local authorities in the UK either imposed an outright ban, or imposed an X (18 years) certificate (effectively preventing the film from being shown, as the distributors said the film could not be shown unless it was unedited and carried the original AA (14) certificate). Certain countries banned its showing, with a few of these bans lasting decades. The film makers used such notoriety to benefit their marketing campaign, with posters stating "So funny it was banned in Norway!". By today's standards though the humor is considered fairly tame.

The film was a box-office success, grossing fourth-highest of any film in the UK in 1979 and highest of any British film in the United States that year. It has remained popular since then, receiving positive reviews and being named 'Greatest comedy film of all time' by several magazines and television networks.

Brian Cohen is born in a stable a few doors from the one in which Jesus is born, which initially confuses the three wise men who come to praise the future King of the Jews. Brian grows up an idealistic young man who resents the continuing Roman occupation of Judea. While attending Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, Brian becomes infatuated with an attractive young rebel, Judith. His desire for her and hatred for the Romans lead him to join the Peoples' Front of Judea (PFJ), one of many fractious and bickering separatist movements, who spend more time fighting each other rather than the Romans.

After several misadventures (including a brief trip to outer space in an alien spaceship), and escaping from Pontius Pilate, the fugitive winds up in a lineup of wannabe mystics and prophets who harangue the passing crowd in a plaza. Forced to come up with something plausible in order to blend in and keep the guards off his back, Brian babbles pseudo-religious truisms, and quickly attracts a small but intrigued audience. Once the guards have left, Brian tries to put the episode behind him, but he has unintentionally inspired a movement. He grows frantic when he finds that some people have started to follow him around, with even the slightest unusual occurrence being hailed as a "miracle". After slipping away from the mob, Brian runs into Judith, and they spend the night together. In the morning, Brian opens the curtains to discover an enormous mass of people outside his mother's house, all proclaiming him the Messiah. Appalled, Brian is helpless to change their minds, for his every word and action are immediately seized as points of doctrine.

Neither can the hapless Brian find solace back at the PFJ's headquarters, where people fling their afflicted bodies at him demanding miracle cures. After sneaking out the back, Brian finally is captured and scheduled to be crucified. Meanwhile, a huge crowd of natives has assembled outside the palace. Pilate (together with the visiting Biggus Dickus) tries to quell the feeling of revolution by granting them the decision of who should be pardoned. The crowd, however, simply shouts out names containing the letter "R", in order to mock Pilate's mispronunciation. Eventually, Judith appears in the crowd and calls for the release of Brian, which the crowd echoes, since the name contains the letter "R". Pilate then agrees to "welease Bwian".

The order from Pilate is eventually relayed to the guards, but in a moment parodying the climax of the film Spartacus, various crucified people all claim to be "Brian of Nazareth" and the wrong man is released. Various other opportunities for a reprieve for Brian are denied as, one by one, his "allies" (including Judith and his mother) step forward to explain why they are leaving the "noble freedom fighter" hanging in the hot sun. Condemned to a long and painful death, Brian finds his spirits lifted by his fellow sufferers, who break into song with "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life"...

Friday, April 22, 2011

RIP: ORRIN TUCKER

Orrin Tucker, big band leader, dies at 100

by Adam Bernstein,

Orrin Tucker, who led a “sweet” big band for nearly a half-century and was best remembered for a coyly suggestive 1939 recording of “Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, Oh!” that featured the baby-voiced singer “Wee” Bonnie Baker, died April 9 near Los Angeles. He was 100, and the cause of death was not reported.

The handsome and personable Tucker enjoyed a remarkably long musical career that began when he formed his orchestra in 1933 and continued through the 1980s as owner of a Hollywood ballroom.

The late jazz critic and historian George T. Simon described Mr. Tucker, a onetime pre-med student who sang and played saxophone, as a “friendly and intelligent” musician who “maintained his equilibrium” after “Oh Johnny” catapulted him to prominence.

“Orrin knew his music, his public and his own limitations,” Simon wrote, “and so, a generation after most of the big bands had faded away, he was still around, still playing his pleasant music in some of the country’s smarter spots.”

Playing the light, undemanding jazz style called sweet, which played down improvisation, Mr. Tucker’s band crested along for decades, recording such tunes as “Billy,” “Would Ja Mind?” and his theme, “Drifting and Dreaming.”

He helped establish Columbia Records as a powerhouse when he dusted off “Oh Johnny,” a song of World War I vintage, and his “girl singer” Bonnie Baker spruced it up with sex appeal.

Emitting mischievous sighs between lyrics, Baker sang of a boy of dubious looks (“You’re not handsome, it’s true”) who more than made up for it in other ways.

Time magazine reported: “So melting and cajoling were diminutive Bonnie’s ‘Oh’s’ (Chicago jitterbugs quickly changed the text to ‘Oh Bonnie, Oh!’) that her record was soon jerking juke-box nickels faster than the fading ‘Beer Barrel Polka.’ ”

After Navy service in World War II, Mr. Tucker formed a new band and tried to change his sound to a brassier style of swing — only to hear from “hotel managers [who] threatened to cancel any return bookings if we didn’t go back to the old sound, which I did,” he said.

After playing himself in the 1975 TV movie “Queen of the Stardust Ballroom,” Mr. Tucker plunged into a new business venture by taking a defunct skating rink and transforming it into the Stardust Ballroom on Sunset Boulevard.

He broadened his repertoire to include songs such as “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,” but he knew his days as a performer were nearing an end. He shut down the ballroom in 1982 and worked in the real estate business in Palm Springs, Calif.

“Orrin Tucker’s death is probably more notable for the longevity that preceded it, as well as for ‘Wee’ Bonnie Baker’s contribution to the band’s success,” said Rob Bamberger, the host of WAMU-FM’s “Hot Jazz Saturday Night” program.

“The wispy sound of the ‘sweet’ bands has not stood up well with time,” Bamberger added, “but Tucker’s band was certainly among the best of its sort.”

Robert Orrin Tucker was born Feb. 17, 1911, in St. Louis, and grew up in Wheaton, Ill. He had an early ambition toward medicine but also was drawn to music as a child when he saw a picture of a shiny saxophone in a Sears Roebuck mail-order catalog.

He moonlighted as a musician while attending North Central College in Naperville, Ill., and found himself in such demand that he formed his own band. He hired singer Evelyn Nelson on trumpeter Louis Armstrong’s recommendation.

“He told me that she sings with a cute voice and that if I wrote cute songs for her, I could make her a star,” Mr. Tucker told the publication Jazz Connection.

He changed her name to Bonnie Baker, which he considered a “name with confidence.” She barely reached 5 feet, prompting Mr. Tucker to introduce her as “Wee” Bonnie Baker.

Mr. Tucker’s first marriage, to fashion model Jill Powell, ended in divorce. In 1975, he married the former Aline Cameron. Besides his wife, survivors include a daughter and a grandson.

“There were so many musicians that said, regardless what the public wants, I’ll play the way I want to play,” Mr. Tucker once reflected. “I’ve always tried to play the music people are fond of and play it the way they want to hear and the way it is easy to dance to. I made it a point to know what the public liked and did my best to please them.”

SOURCE

Thursday, April 21, 2011

BOOK REVIEW: MARLENE - A PERSONAL BIOGRAPHY

The strength of Chandler's approach is that each luminary's version of history is recorded in lengthy interviews, from which she quotes extensively. Friends, colleagues, ex-lovers, relatives are also cited. Chandler's non-threatening style makes each subsequent, aging legend more likely to speak with her. Unfortunately, she rarely challenges any of their assertions.

Although most major classic Hollywood figures adeptly managed their images, few did so as tenaciously as Dietrich (1901-92). She perpetuated myths about herself from the beginning of her American career. Decades into her stardom, she claimed she had been "a student in a theatre school in Europe" when director Joseph von Sternberg cast her as Lola Lola in The Blue Angel (1930), making her an international sensation. She implied she was young and inexperienced. Researchers eventually uncovered the truth. While she had briefly studied with Max Reinhardt, she was 29, had made at least 17 German movies beginning in 1923, and had worked in cabaret and the stage in Berlin and Vienna. Von Sternberg saw something in her others hadn't. Dietrich insists she never tried to hide her age and didn't discuss those early pictures because they weren't important. It's a convenient if unlikely excuse.

After the success of The Blue Angel, Paramount signed Dietrich to a long-term contract, and from 1930-35, von Sternberg directed her in another six movies, the last four financial failures. They are nonetheless riveting, superbly framing Dietrich's enigmatic mystique. She continued making films without him for nearly three decades, often to great effect, but her place in the Hollywood Pantheon is based on their collaboration. Their relationship was contentious – he was often abusive, yet she spoke of him glowingly.

She reminisces about her upper-middle-class Berlin childhood, her devotion to daughter Maria Riva, her grandchildren and only husband, Rudolph Sieber. Once she arrived in America, she and Sieber rarely lived together – he had a mistress whom Dietrich liked – and for much of the time, they looked after Maria.

She touches on some of her affairs: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., who speaks warmly about her; John Wayne; Jean Gabin; and writer Mercedes De Acosta. The last is discussed briefly within the context of her lesbian experiences, which started with a slightly older classmate. Dietrich says she had a "brief encounter" with De Acosta, who also had an intimate relationship with Greta Garbo, whom Dietrich found "fascinating." Yet Chandler fails to pursue that topic. She mentions that Dietrich had a small role in Joyless Street (1925), starring Garbo. The two may have had a scene together. Chandler doesn't ask if they met, and ignores Diana McClellan's assertion in The Girls that Dietrich may have seduced Garbo.

Chandler's on sounder footing when Dietrich explains why for years she didn't admit to having an older sister, of whom she was fond. When Hitler came to power, he ordered Dietrich to return to Germany. She refused, becoming an American citizen instead. Her mother, sister, brother-in-law and nephew remained in Germany, and publicity about them would have been risky. Her brother-in-law and sister cooperated with the Nazis, but after the war, Dietrich suppressed that information, and relocated her family to West Berlin.

Surprisingly, Chandler doesn't spend much time on Dietrich's courageous appearances before Allied soldiers at the European front during WWII. She was made a Colonel and carried cyanide on her, in case she was captured. Despite grueling conditions, she sang for GIs, talked to them, wrote letters for them, visited the wounded, and when possible, cooked for them.

One of the best parts of Marlene recounts how, after a 13-year absence, in 1977, she made her last screen appearance, directed by David Hemmings in Just a Gigolo, starring David Bowie. Screenwriter Joshua Sinclair defied all odds to sign her. She was offered $100,000 for four days' work in Berlin. She demanded – and received – $250,000 for two days' shooting in Paris, plus the cost of her dress ($5,000). The movie was awful, but she performed the title song hauntingly.

In the early 1980s, growing more dependent on alcohol and pain medication, Dietrich became a recluse in her Paris apartment, ordering room service from the Plaza Athenee Hotel. She had always spent lavishly, on jewels, clothes, her daughter's townhouse on Manhattan's Upper East Side, her four grandsons' private-school education. Sadly, she began to outlive her money.

In movies and her acclaimed cabaret and concert acts, Dietrich controlled every aspect of her image, and was determined to do so late in life. Chandler assists her ably in that regard. For a more balanced view of her remarkable career, readers should turn to Maria Riva's Marlene Dietrich, or Stevan Bach's Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend, or watch Maximilian Schell's amazing documentary Marlene (1984), in which she refuses to appear on camera, but answers his questions with imperious asperity.

SOURCE

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

PHOTOS OF THE DAY: ODD PAIRINGS

Sunday, April 17, 2011

SPOTLIGHT ON TERESA WRIGHT

Wright was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her screen debut in The Little Foxes (1941). The following year, she was nominated again, this time for Best Actress for The Pride of the Yankees, in which she played opposite Gary Cooper as the wife of Lou Gehrig; that same year, she won Best Supporting Actress as the daughter-in-law of Greer Garson's character in Mrs. Miniver. No other actor has ever duplicated her feat of receiving an Oscar nomination for each of her first three films.

In 1943, Wright was loaned out by Goldwyn for the Universal film Shadow of a Doubt, directed by Alfred Hitchcock. She played an innocent young woman who discovers that her beloved uncle, played by Joseph Cotten, is a serial murderer. In my humble opinion it was her best work ever. Other notable films include The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), an award-winning film about the adjustments of servicemen returning home after World War II, and The Men (1950), another story of war veterans, which starred Marlon Brando.

Wright rebelled against the studio system of the time. When Samuel Goldwyn fired her, citing her refusal to publicize the film Enchantment (1948), she expressed no regret about losing her $5,000 per week contract. She said, "The type of contract between players and producers is, I feel, antiquated in form and abstract in concept... We have no privacies which producers cannot invade, they trade us like cattle, boss us like children." However, before a March 2006 screening of Enchantment on Turner Classic Movies, host Robert Osborne said that Wright did later have some regrets about leaving Goldwyn, since her salary per film went from $125,000 under Goldwyn to about $25,000 per film afterwards.

After 1959, she worked mainly in television and on the stage. She was nominated for Emmy Awards in 1957 for The Miracle Worker and in 1960 for The Margaret Bourke-White Story. She was in the 1975 Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman and the 1980 revival of Morning's at Seven, for which she won a Drama Desk Award as a member of the Outstanding Ensemble Performance.

Her later movie appearances included a major role in Somewhere in Time (1980) and the role of Miss Birdie in John Grisham's The Rainmaker (1997), directed by Francis Ford Coppola.On March 6, 2005 she died of a heart attack at Yale-New Haven Hospital in Connecticut at the age of 86...

Friday, April 15, 2011

CHARLIE CHAPLIN AND GOOGLE

When clicked, the logo, known as the "Google doodle," plays a silent film featuring members of the doodle team acting out Chaplin-esque sketches.

Google said the doodle honoring Chaplin, who was born on April 16, 1889, is its first live-action video and was created by the Google doodle team with help from the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum.

"We hope that our homage gets people talking about his work and the many virtues of silent film," Google "doodler" Ryan Germick said in a blog post.

The Mountain View, California-based Google frequently changes the colorful logo on its famously spartan homepage to mark anniversaries or significant events or pay tribute to artists, scientists, statesmen and others.

SOURCE

Thursday, April 14, 2011

RIP: ARTHUR MARX

As a child Mr. Marx spent several years on the road with Groucho Marx and the rest of the Marx Brothers’ vaudeville act — Chico, Harpo, Gummo and later Zeppo — before enjoying a celebrity-filled youth in Los Angeles as the brothers rose to stardom.

His own show-business career was varied and long, writing Hollywood screenplays and scripts for some of television’s most popular sitcoms.

But his father’s life and career provided Mr. Marx with perhaps his richest source of material. “Life With Groucho,” published in 1954, captivated readers with its sharp but affectionate portrait of Groucho — who peppered the narrative with kibitzing footnotes — and its shrewd account of the show-business milieu in which he thrived. A sequel, “Son of Groucho,” was published in 1972.

Mr. Marx and Robert Fisher, a former writer for Groucho, also wrote the book for a 1970 Broadway musical about the Marx Brothers, “Minnie’s Boys,” with Shelley Winters in the lead role of Minnie Marx, and “Groucho: A Life in Revue,” which was produced Off Broadway in 1986.

Taken together, Arthur Marx’s two books about his father offered a bittersweet picture of life in the Marx home. He described himself as desperate both to escape from his father’s shadow and to please him, an impossible task. The comic genius who kept millions in stitches was, in his private life, miserly and emotionally distant.

“No matter how much he loves you, he’ll rarely stick up for you,” Mr. Marx wrote in “Son of Groucho.” “He’ll make some sort of wisecrack instead to keep from getting involved. It’s a form of cowardice that can be more frustrating than his monetary habits.”

When “Life With Groucho,” which was much sunnier than the sequel, was being serialized in The Saturday Evening Post, Groucho denounced it as “scurrilous” and threatened legal action unless substantial changes were made.

Arthur sent him a phony set of galley proofs with the requested changes but had the book published as written. Groucho never brought the matter up again.

In 1974, Arthur Marx became embroiled in a legal battle to block the appointment of his father’s longtime companion, Erin Fleming, as the conservator of his estate. Lurid court testimony depicted Ms. Fleming as a controlling, abusive caretaker, and a superior court judge eventually appointed Andy Marx, Arthur’s son, to replace her. Groucho died a little more than a month after that, on Aug. 19, 1977.

Arthur Julius Marx was born in Manhattan on July 21, 1921. After his family moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s he gained renown as a tennis player, achieving national ranking while still in high school and playing on the junior Davis Cup team in 1939 with the future stars Jack Kramer, Ted Schroeder and Budge Patty. As a student at the University of Southern California, he competed in national tournaments.

After serving with the Coast Guard in the Philippines during World War II, he returned to Los Angeles and found work as a reader at MGM. He soon turned his hand to screenwriting. He wrote scripts for the 1947 Blondie film “Blondie in the Dough” and several popular short films narrated by Pete Smith.

He later teamed up with Mr. Fisher to write the screenplays for the Bob Hope films “Eight on the Lam,” “A Global Affair,” “I’ll Take Sweden” and “Cancel My Reservation.”

The two went on to write for television sitcoms, including “McHale’s Navy,” “Petticoat Junction, “My Three Sons,” “All in the Family,” “The Jeffersons” and “Maude.” They wrote 41 episodes of the sitcom “Alice” from 1977 to 1981.

Mr. Marx used his tennis experiences as background for a novel, “The Ordeal of Willie Brown” (1951), about an unsavory tennis bum, and his lighthearted magazine articles about his young family were gathered into a comic memoir, “Not as a Crocodile” (1958). At the time, he was married to Irene Kahn, the daughter of the songwriters Gus and Grace Kahn. (Mr. Marx and Ms. Kahn later divorced.)

In addition to his family memoirs, Mr. Marx wrote several show-business biographies, including “Goldwyn: A Biography of the Man Behind the Myth,” “Red Skelton,” “The Nine Lives of Mickey Rooney” and “The Secret Life of Bob Hope.” His joint biography of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, “Everybody Loves Somebody Sometime (Especially Himself),” published in 1974, was made into a television movie, “Martin and Lewis,” in 2002.

With Mr. Fisher, he also wrote the comedy “The Impossible Years,” which opened on Broadway in 1965 with Alan King in the starring role of a harried psychiatrist with two teenage daughters. It ran for 670 performances.

In addition to his sons Steve, of Seattle, and Andy, of Los Angeles, he is survived by his wife, Lois; a stepdaughter, Linda Donovan of Pleasant Hill, Calif.; two sisters, Miriam Allen of San Clemente, Calif., and Melinda Berti of Mendocino, Calif.; four grandchildren; and two step-grandchildren.

THE GENUIS OF ERNIE KOVACS

By FRAZIER MOORE, AP Television Writer

NEW YORK – If you have ever laughed at, say, David Letterman or "Monty Python's Flying Circus" or "Laugh-In" or "Saturday Night Live" or Steve Allen or Craig Ferguson, then you owe a debt to Ernie Kovacs. After more than 50 years, he remains the wellspring of TV as an instrument of humor and delighted innovation.

Sadly, much of Kovacs' work is gone. In the 1950s, most shows weren't preserved after airing. Prerecorded shows were routinely erased so the tape could be reused for the next thing.

But a new six-disk boxed set, "The Ernie Kovacs Collection," curates surviving treasures from Kovacs' prodigious TV output stretching from 1951 through his untimely death in 1962. (Distributed by Shout! Factory, it will be released April 19, listed at $54.99.)

These precious samples, lovingly recovered and restored, provide startling glimpses of the birth of television — even TV as we watch it today, rejiggered and recycled by Kovacs' disciples long after his passing. Kovacs marks where TV started, and he has never been eclipsed as a TV visionary.

A native of Trenton, N.J., he was an aspiring-actor-turned-radio-personality when, in 1950, he landed a job at a local Philadelphia TV station. There he hosted wacky fashion and cooking programs, as well as the first-ever TV wake-up show (an unwitting prototype of NBC's "Today," which would debut nationally in 1952).

No recordings exist of these earliest efforts, but they gave Kovacs his providential entry to a video wonderland where, to him, the creative possibilities must have seemed limitless.

"The Ernie Kovacs Collection" kicks off with a March 7, 1951, edition of "It's Time for Ernie," a live, local afternoon show.

Radiating buoyancy, amusement, his signature mustache and cigar, Kovacs is clearly in synch with his TV playground. He is as adept at freeform foolishness as at masterminding a meticulously crafted gag. And he never shrinks from the offbeat or conceptual. In the midst of his riffing he throws open the studio doors to take a leisurely stroll down a long corridor into the distance, for a sip from a water fountain. Then he makes his way back into the studio and continues where he left off.

In another off-the-cuff moment, he begins dusting his props-cluttered set, then, moving offstage, turns his attention to a TV camera, whose lens he scrubs with his dust cloth.

"You're putting on weight," he chuckles at the viewer through the lens.

TV had hardly begun, and already Kovacs was giving viewers a peek behind TV's artifice, inviting the audience to join him on the inside.

Instinctively, Kovacs understood what none of his TV contemporaries had guessed, and what few in the business acknowledge today: TV isn't an extension of radio, cinema, vaudeville or theater. As a writer-producer-performer, Kovacs knew that TV begged to be something unique. His happy job was to figure out what.

To do it, Kovacs surrounded himself with an evolving troupe of fellow players (often including his wife, the singer-actress Edie Adams), and, as his budget allowed, musicians, dancers and fancier production. But some things never changed: From his first days on TV he claimed the ragtime-y "Oriental Blues" as his lifelong theme song.

The collection includes five half-hour prime-time specials Kovacs produced for ABC in 1961. (The last aired in January 1962, just 10 days after he died at age 42 in a car crash near his home in Beverly Hills, Calif.)

There are moments in these shows whose level of invention and avant-garde abandon not only holds up today, but may have never been excelled on TV since they were taped. In one sketch, a fellow grows increasingly annoyed by a kids TV host, "Freddy the Friendly Fireman." Finally the viewer raises a pistol and fires. Pan to the TV: Freddy, shot dead, is draped out of the TV screen into the viewer's living room. In one of Kovacs' music videos (an art form he apparently pioneered) a high-stakes poker game is set to the beginning of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

Kovacs loved music, but also experimented with silent bits. He was sophisticated, but loved to show things unexpectedly crashing through the floor. He would stage extended pieces or quick visual puns. He loved when things went wrong.

His taste for the absurd was reflected in a bit that may remain his best-known: the Nairobi Trio. Three people costumed in gorilla suits, bowlers and long overcoats mechanically mime to a tune like wind-up toys, with one of them (played by Kovacs) repeatedly thwacked on the head with a timpani mallet by a fellow gorilla.

It was delightfully low-tech. But Kovacs was also ever on the lookout for ways to make TV, however primitive in those days, do extraordinary things. He came up with a simple device that allowed the picture to tilt or even spin, which served some of his comedy bits. He introduced an early form of the "green screen" effect, enabling a married man's "invisible girlfriend" to conveniently vanish from sight after taking off her clothes.

By today's standards, the TV equipment of the 1950s, and even early 1960s, was cumbersome and confining. But not for Kovacs, whose imagination made TV soar. To watch him at any phase of his career is to see a man at play. At times his care is painstaking, but there's no pain. He finds joy in every idea. For him, TV was too important to be serious about it.

As surveyed by this DVD collection, Kovacs' career spanned little more than a decade, with his many shows popping up on numerous networks at every hour until, a half-century ago, it was cut short, denying him the measure of stardom he deserved.

He did TV his way for a cult of Kovacs-worshippers, and left an imprint on TV that continues to be recognized by people who don't even know his name.

But oddly enough, there has been little acceptance or inspiration for advancing the cause he championed: broadcast video as an art form. This DVD treasury celebrates Kovacs as TV's first video auteur — and, thus far, arguably its last.

SOURCE

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

BASEBALL MEETS HOLLYWOOD

Baseball has been a rich subject for movies since the game's (and cinema's) earliest days. On occasion, baseball players themselves took a swing at being Hollywood stars themselves. Most were strictly minor league as actors, but a few nearly hit a home run.

Here's a lineup of baseball giants who tried their luck in front of the camera:

BABE RUTH

The Sultan of Swat was the subject of a dreadful 1948 biopic, "The Babe Ruth Story," starring a totally miscast William Bendix, but the real Ruth appeared in several films and shorts during his years with the New York Yankees. Babe was just 25 and a recent acquisition from the Boston Red Sox when he made his film debut — billed as George Herman "Babe" Ruth — in the 1920 film "Headin' Home." The comedy offers a semi-fictitious look at how the Babe became a baseball player. The white-pancake makeup the Babe wears in the movie gives him almost a zombie-esque quality. Though the film isn't much, he has charm to spare.

But he's even better in the 1928 Harold Lloyd silent comedy "Speedy." He's one of the passengers in Lloyd's taxi cab, and he plays himself to perfection. In 1942, the Babe was funny and poignant as himself in "The Pride of the Yankees," the wonderful true story about his Yankees teammate Lou Gehrig (Gary Cooper).

LOU GEHRIG

Speaking of the Iron Horse, the Yankees' star first baseman went Hollywood in 1938, the year before ALS felled his career, in a contemporary western called "Rawhide." Gehrig was tall, muscular and just as handsome as Cooper, who would play him in "The Pride of the Yankees." But he isn't much of a thespian — his New Yawk accent is pretty strong — and "Rawhide" isn't much of a movie, but any Gehrig fan will want to check it out. Ironically, the film's producer, Sol Lesser, had signed Gehrig to play Tarzan, but Lesser later said that "when [Gehrig] stripped his Yankee uniform for a leopard skin, two things became apparent. Both were Gehrig's legs: pillars of strength befitting baseball's iron man, their piano construction was functional rather than decorative."

JACKIE ROBINSON

The Brooklyn Dodger created history when he broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947. And three years later, he starred as himself in the low-budget but moving biopic "The Jackie Robinson Story." Dodgers President Branch Rickey insisted that Robinson be cast as himself. Though he had never acted before, Robinson isn't too awkward in front of the camera, and having a young Ruby Dee play his wife, Rachel, probably aided his performance. The Hollywood Reporter stated that though "the film is choppy, episodic … director Alfred E. Green and his star maintain a serene dignity throughout it all."

MICKEY MANTLE and ROGER MARIS

The New York Yankees stars appeared in two films in 1962, not long after Maris broke Ruth's home run record by hitting 61 in 1961. In the Cary Grant-Doris Day sex comedy "That Touch of Mink," Mantle and Maris play themselves and interact briefly with Grant and Day, who have dugout seats for the game at Yankee Stadium. They're pretty stiff in the cameo, but in the family film "Safe at Home!" they are as rigid as a 10-day-old piece of dried-out chewing tobacco. Bryan Russell plays a motherless boy who tells his Little League team he is great friends with the Yankees' sluggers, then heads out to persaude them to come meet his team. William Frawley in his last film role, playing the Yankees manager, is the best thing about it.

SOURCE

Monday, April 11, 2011

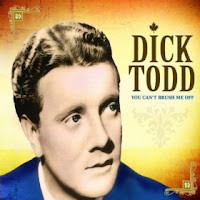

FORGOTTEN ONES: DICK TODD

Handsome and husky-voiced, romantic baritone Dick Todd was also dubbed King of the Jukebox. During his brief heyday from 1938-1942, Todd recorded about 200 songs for RCA Victor's Bluebird imprint, enabling him to compete with Decca's main attraction (Crosby) and Okeh's Buddy Clarke. Each of these dashing devils could be heard for the budget-line price of just thirty-five cents for each 78 rpm record, or seventeen and a half cents per song.

Dick Todd's story would make an excellent old-fashioned motion picture, preferably filmed in 16 mm black-and-white. Born on August 4, 1914 on a farm near Calgary, Alberta, Canada, he was the son of a retired military officer who moved the family to Montreal around 1926. Todd played the trumpet and sang, first in school and then at the Belmont Amusement Park with a small band led by George Sims. This led to steady work at a nightclub at Lake Champlain called the Meridian. After lukewarm attempts to earn degrees in agriculture and engineering, Todd directed his energies towards putting songs across over the radio and doing commercials for Maxey Baking Powder. Backed by his own quintet (including trombonist and alto saxophonist Murray McEachern), Todd sang and blew his trumpet on cruise ships in the Caribbean during the tourist season. All of this activity paid off when he found himself signing his first Victor contract in Montreal.

In 1936 he recorded several pop tunes including "I'm an Old Cowhand" and "Girl in a Bonnet of Blue." After Sims' group was taken over by Ted Large of the Five Large Brothers, Todd began performing almost exclusively in the broadcast studio backed by orchestras under the direction of Lucio Augustini and Alan McIver. It was these programs, which aired during the years 1937-1938, that enabled Dick Todd to develop a following among radio audiences in the northeastern United States.

In 1940 Dick Todd appeared in the series Showboat with Nadine Connor and Virginia Verrill, with Paul LaValle on the Chamber Music Society of Lower Basin Street show, and sang "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" in a film short with Richard Hayman. For a little while he hosted his own program. Dick Todd's biggest hits from this period include "Blue Orchids," "Deep Purple," "To You, Sweetheart, Aloha," "All This and Heaven Too," and "The Gaucho Serenade." When it was time for Todd to serve as a Canadian citizen in the Second World War he generously set up Ted Weems' crooner Perry Como as his replacement at Victor.

Like most everyone who worked in showbiz, Dick Todd devoted himself to entertaining the troops during wartime. Afterwards, his career began to slip into a gradual but steady decline that would end in utter obscurity and abject poverty. In 1945 he replaced Lawrence Tibbet on Your Hit Parade and shared the microphone with Joan Edwards, but was given the boot in January 1946 to make way for Johnny Mercer. Not to be deterred, Todd signed on with the Larry Sunbrook Circus, barking endless streams of blarney as Master of Ceremonies and singing while riding a horse (a skill he'd developed while growing up in Alberta).

In the late 1960s, Dick also made appearances on Joe Franklin nostalgia show. Two disorders that brought him down were chronic alcoholism and debilitating arthritis. He was last seen working as a stagehand among the ropes behind the scenes at the Ed Sullivan Show at the Coliseum and at Studio 50 in New York. From there he is believed to have hit the skids and become a homeless wino. The last known sighting of Dick Todd was in a VA hospital in 1973, where was interviewed for an LP collection of his hits.

The circumstances, date, and location of his death was never established until his son finally revealed that his father died homeless in 1973, and his ashes were scattered into the ocean near New York. Todd's son held on to the information until 1999 due to his estrangement to his father.

While Dick Todd definitely had a way with a song, unfortunately his private life was never that melodic. He died alone and forgotten - but his many excellent recordings never will fade away...

Saturday, April 9, 2011

RIP: SIDNEY LUMET

Sidney Lumet, the director behind American movie classics such as 12 Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon and The Verdict, died Saturday. He was 86.

Lumet died from lymphoma at his home in New York City his stepdaughter, Leslie Gimbel, tells The New York Times.

The film director, famous for creating art impassioned by social justice and satire, told The Times in 2007 that he made movies not as an attempt to change the world, but for his own love of the field.

"I do it because I like it," he said. "And it's a wonderful way to spend your life."

But his films, which painted portraits of real issues such as corruption and justice, did just that. His movies received 46 Academy Award nominations throughout his career. Although he never personally won the honor for Best Director – which was remedied in 2005 with an honorary award from the Academy – six of his films won Oscars during the peak of his career, between 1974 and 1976. Lumet himself was nominated for Best Director for The Verdict, Network, 12 Angry Men and Dog Day Afternoon.

Lumet, despite having a very Hollywood career, was a New Yorker at heart, and the city he loved was the backdrop for many of his greats, including Serpico (1973) and The Pawnbroker (1964).

"Locations are characters in my movies," he said. "The city is capable of portraying the mood a scene requires."

New York seemed to be his most constant love affair. His first three marriages – to actress Rita Gam (1949-1954), socialite Gloria Vanderbilt (1956-1963) and the daughter of Lena Horne, Gail Jones (1963-1978) – ended in divorce. In 1980 he married Mary Gimbel.

He is survived by Gimbel, his two daughters from his marriage with Jones (Amy and Jenny Lumet), his stepdaughter Leslie Gimbel, his stepson Bailey Gimbel, nine grandchildren and a great grandson...

Friday, April 8, 2011

THE LEGACY OF BETTE DAVIS

“In this business,” Bette Davis once said, “until you're known as a monster you're not a star.” There was no denying Bette Davis’ stardom – she appeared in more than 100 films, won the Academy Award twice, set a record by being nominated 10 times, was the first woman to be given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the American Film Institute, and was the first to serve as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

But it’s safe to say Bette Davis made a few enemies along the way.

In Davis’ day it could be difficult (as it remains now) to distinguish real animosity from publicity stunts dreamt up by studio marketing executives, but the public was so willing to believe Bette Davis a monster in part because, unlike many actresses, she didn’t shy away from unsympathetic roles.

Indeed, her big break came in playing the vicious, illiterate waitress Mildred Rogers who torments club-footed obsessive Phillip Carey in Of Human Bondage. She received her first Academy Award nomination and was considered a shoo-in but was beaten by Claudette Colbert in what many rank among the worst Oscar snubs of all time. The controversy resulted in the accounting firm Price Waterhouse being hired to tally the votes the following year, a practice that continues to this day.

In a positive review of her next film, 1935’s Dangerous, one critic wrote of her portrayal of a troubled actress, “I think Bette Davis would probably have been burned as a witch if she had lived two or three hundred years ago. She gives the curious feeling of being charged with power which can find no ordinary outlet.” She won an Academy Award for the role.

Her second Academy Award came for a role in Jezebel, and it sparked one of two high-profile catfights that Bette Davis would become famous for. She landed the Jezebel part originally played on Broadway by Miriam Hopkins, and while on the set of The Sisters, had an affair with director Anatole Litovak – Hopkins’ husband. The women were then cast together in The Old Maid playing – what else – two women warring over the same man. Hopkins and Davis posed for publicity stills wearing boxing gloves and the stunt pairing was repeated in Old Acquaintance. One is tempted to brush the whole feud off as a publicity stunt – but not Davis. She continued to slam Hopkins as “unprofessional” and “terribly jealous” in interviews decades later.

That was practically a compliment compared to what she had to say about Joan Crawford.

That Bette Davis and Joan Crawford didn’t like each other is an understatement. It may have began when Crawford had great success with two films originally meant for Davis – Mildred Pierce, which Davis passed on to star in The Corn is Green, and Possessed, which Davis missed as she was on maternity leave (the role earned Joan Crawford an Oscar nomination).

The two actresses temporarily put their differences aside to star in the Robert Aldrich-directed thriller about disabled, former big-time actress Blanche Hudson living in a decaying mansion and being tormented by her psychotic sister, a former child star known as ‘Baby’ Jane. Said director Aldrich of their pairing, “It's proper to say that they really detested each other, but they behaved absolutely perfectly."

Well, not exactly.

Davis, aware that Crawford was on the Pepsi-Cola Board of Directors (her late husband had been Pepsi’s CEO), insisted on having a Coca-Cola machine installed in her dressing room. While filming a fight scene, Davis kicked Crawford in the head. Crawford retaliated by concealing weights under her gown during a scene where Davis had to drag her across the floor, causing the latter actress to strain her back.

When Davis was nominated for an Academy Award for the role, Crawford reputedly campaigned against her, even going so far as to contact Bancroft and offer to accept the Best Actress award in her honor should she be unable to attend the ceremony. In the end, Crawford did just that, and the two actresses would publicly exchange barbs for decades. Hoping to repeat Baby Jane’s successful formula, Aldrich again cast the pair in Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte, but Crawford dropped out after a campaign of intimidation by Davis and was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown.

For the rest of her life, Davis would go out of the way to slam Crawford, and is famously quoted as saying, “Why am I so good at playing bitches? I think it’s because I am not a bitch. Maybe that’s why Miss Crawford always plays ladies.”

It wasn’t just ladies Bette Davis tangled with. She clashed with director William Wyler, with Errol Flynn, with Robert Montgomery, with Warner Brothers, and even with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences while serving as its president. She seemed to revel in the notoriety and enjoyed being bluntly dismissive, swearing and chainsmoking through talk shows where she became a frequent and popular guest. Audiences enjoyed her candor and she was a link to the bygone days of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Bette Davis continued acting on screen and stage almost right up until her death in 1989. Asked how she managed to enjoy such a long, tumultuous career, she responded matter-of-factly, “I survived because I was tougher than everybody else.”

SOURCE

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

DEBBIE REYNOLDS AT 79

"They always want to know how I forgave Elizabeth (Taylor) and they ask if I'm getting along with (daughter) Carrie (Fisher). They might ask me to sing `Tammy,' too," Reynolds said, chuckling, during a phone interview from her Los Angeles home last week.

"The gossip comes before the work. But that's always true in a movie star's life," the actress added.

On Sunday, April 10, Connecticut fans will have a chance to meet and question the 79-year-old star when she appears at the Edgerton Center on the campus of Sacred Heart University in Fairfield.

The evening will include clips from an amazing film career that began in the 1950s with such classics as "Singin' in the Rain," soared through the 1960s with hits like "The Unsinkable Molly Brown" (for which Reynolds was Oscar-nominated) and continues with select acting jobs, such as the forthcoming Katherine Heigl comedy "One for the Money."

The star will do an onstage "Inside the Actors Studio"-style interview with Jerry Goehring, executive director of the Edgerton Center, and then field questions from the audience.

Reynolds believes she has always had the big advantage of being a performer the public simply likes.

"They treat me the way they would an aunt or a sister because they know my whole personal life. It's always been exposed. People tend to want to protect me.

"I think I've traveled to a different state every month of my life for 65 years and I've never met a stranger. When I meet new people they're like family, so I never consider their questions rude," she said.

A few days before we talked, Reynolds did a lot of TV interviews following the death of Taylor in which she spoke about how they had healed their rift many years ago (after then-husband Eddie Fisher left Reynolds for Taylor in one of the great tabloid events of the late 1950s).

Reynolds said she is surprised that people are surprised she could forgive Taylor.

"You have a choice in life to hold on to something or move on. If you have any intelligence at all, when a man moves on you have to let him go," she said.

As for Taylor being the woman who "stole" Fisher from Reynolds, the star said, "You can entice a man all you want, but if that man loves his wife, he might have a fling, but he'll come back. That was not the case in my situation.

"You have to grow up," she said of accepting the unpleasant hands life deals you. "It takes some experience but you just have to get over it and move along."

As a young contract player at MGM in the 1950s, Reynolds often had to swallow her pride and simply go to work despite knowing that some of her directors weren't too crazy about being forced to use the actress.

Early on, Reynolds showed the ability to play drama -- as well as comedy and musicals -- when she held her own opposite Bette Davis and Ernest Borgnine in the 1956 Paddy Chayefsky-scripted, Bronx-set story, "The Catered Affair."

"I was lucky to get to do it because the director didn't want me in it," she said of Richard Brooks. "Bette and Ernie were the ones who really directed me," Reynolds added. "(The director) just kept calling me `Miss Hollywood.' "

One of Reynolds' best pictures of the 1960s was the acerbic comedy "Divorce American Style" (1967), in which she co-starred with Dick Van Dyke and Jason Robards. It was a sophisticated treatment of marriage and divorce that paved the way to even more daring films such as "Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice" two years later.

Again, the film's director, Bud Yorkin, didn't want Reynolds in his movie.

"I don't know why he didn't want me, but I had to read for him. Dick Van Dyke and everyone else were happy with me, but he (Yorkin) didn't think I understood (the material) until after the rushes started to come in."

Today, Reynolds faces a very difficult decision in her life -- auctioning off the mammoth collection of movie memorabilia she has been storing away.

The collection began with Reynolds stepping in and purchasing the MGM holdings that were about to be dumped in 1970 -- when new management at the studio decided to divest itself 0f its own history -- and continued with other important finds (ranging from Marilyn Monroe's "subway dress" in "The Seven Year Itch" through set pieces from "Cleopatra").

Valued at more than $20 million, the collection was always intended to go to a museum devoted to Hollywood history, but that didn't happen.

"It was a very hard decision, but I could never get the industry in back of it," the star said.

Reynolds began to choke up as she talked about the Los Angeles auction coming up in June.

"I'm just trying to get through it ... but I know that I have to open another door and walk another path."

SOURCE