Taking his mother's maiden name, DeRita, the actor joined the burlesque circuit during the 1920s, gaining fame as a comedian. During World War II, DeRita joined the USO, performing through Britain and France with such celebrities as Bing Crosby and Randolph Scott. In the 1944 comedy film The Doughgirls, about the housing shortage in wartime Washington, D.C., he had an uncredited role as "the Stranger", a bewildered man who repeatedly showed up in scenes looking for a place to sleep.

The Three Stooges (Curly Howard, Larry Fine, and Moe Howard) had been making short comedies for Columbia Pictures since 1934. Curly suffered a disaling stroke on May 6, 1946, forcing him to retire. He died on January 18, 1952 at the age of 48. His brother Shemp Howard, the original third Stooge before leaving the act in 1932 for a solo career, only wanted to be a temporary replacement. Joe DeRita was also starring in his own series of shorts at Columbia (in The Good Bad Egg, Wedlock Deadlock, Slappily Married, and Jitter Bughouse). Stooges producer-director Jules White attempted to recruit Joe DeRita for the Three Stooges, because he wanted "another Curly." However, the strong-willed DeRita refused to change his act or imitate another performer, and White eventually gave up on DeRita (DeRita's own short-subject contract was not renewed after four films, the final entry being Jitter Bughouse). DeRita returned to burlesque and recorded a risque LP in 1950 called Burlesque Uncensored.

When Shemp Howard died unexpectedly of a heart attack on November 22, 1955 at age 60, he was succeeded by Joe Besser. Columbia eventually shut down the short-subjects department at the end of 1957, and Besser quit the act to take care of his ailing wife. The two remaining Stooges seriously considered retirement. Then Columbia's television subsidiary, Screen Gems, syndicated the Stooges' old comedies to television, and the Three Stooges were suddenly television superstars.

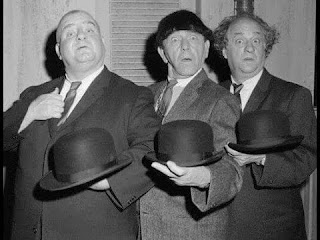

Moe and Larry now had many job offers, but they were in need of a "third Stooge." Larry had seen DeRita in a Las Vegas stage engagement and told Moe that DeRita would be "perfect for the third Stooge." Howard and Fine invited DeRita to join the act, and this time he readily accepted. When he first joined the act in 1958 (shortly after appearing in a dramatic role in the Gregory Peck western, The Bravados), DeRita wore his hair in a style similar to that of former Stooge Shemp Howard and did so during initial live stage performances. However, with television's restored popularity of the Three Stooges shorts featuring Curly Howard, it was suggested that Joe shave his head in order to look more like "Curly". At first, DeRita sported a crew cut; this eventually became a fully shaven head. Because of his physical resemblance to both Curly and Joe Besser, and to avoid confusion with his predecessors, DeRita was renamed Curly Joe.

The team embarked on a new series of six theatrical Three Stooges films, including Have Rocket, Will Travel (1959), DeRita's on-screen debut with the Stooges, and Snow White and the Three Stooges (1961). Aimed primarily at children, these films rarely reached the same comedic heights as their shorts and often recycled routines and songs from the older films. (Moe and Larry's advanced ages - Moe was 62 and Larry 57 at the time of the first Curly Joe film - plus pressure from the PTA and other children's advocates, led to the toning-down of the trio's trademark violent slapstick.) While DeRita's physical appearance was vaguely reminiscent of the original "Curly", his characterization was milder and not as manic or surreal. The characterization evolved over time; early sketches featuring Curly Joe (such as a commercial for Simoniz car wax) have him effectively as a fifth wheel while Moe and Larry divided most of the comedy between themselves, while by the mid-1960s, Larry's role had been reduced and Curly Joe divided much of the comedy with Moe. Curly Joe also showed a bit more backbone, even occasionally talking back to Moe, calling him "buddy boy".

The Stooges eventually folded in 1970 when Larry Fine suffered a stroke, although Moe always had dreams or recreating the group. In 1974, with Moe's blessing, DeRita attempted to form a truly "new" Three Stooges. He recruited burlesque and vaudeville veterans Mousie Garner and Frank Mitchell to replace Moe and Larry for nightclub engagements. However, they were poorly received thereby ending the group. Mitchell had worked with original Stooges organizer Ted Healy decades earlier in an abortive attempt to replace the Stooges after they had split from Healy. Mitchell had also replaced Shemp as the "third stooge" in a 1929 Broadway play.

On July 3, 1993, the last surviving Stooge, Joe DeRita died of pneumonia nine days before his 84th birthday at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California. DeRita is interred in a grave at the Pierce Brothers Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood, California; his tombstone reads "The Last Stooge"...