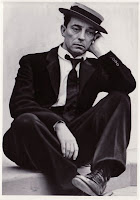

Here is part two of our three part series on the life and talent of the great Buster Keaton...

In February 1917, Keaton met Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle at the Talmadge Studios in New York City, where Arbuckle was under contract to Joseph M. Schenck. Joe Keaton disapproved of films, and Buster also had reservations about the medium. During his first meeting with Arbuckle, he asked to borrow one of the cameras to get a feel for how it worked. He took the camera back to his hotel room, dismantled and reassembled it. With this rough understanding of the mechanics of the moving pictures, he returned the next day, camera in hand, asking for work. He was hired as a co-star and gag man, making his first appearance in The Butcher Boy. Keaton later claimed that he was soon Arbuckle's second director and his entire gag department. Keaton and Arbuckle became close friends.

In 1920, The Saphead was released, in which Keaton had his first starring role in a full-length feature. After Keaton's successful work with Arbuckle, Schenck gave him his own production unit, Buster Keaton Comedies. He made a series of two-reel comedies, including One Week (1920), The Playhouse (1921), Cops (1922), and The Electric House (1922). Based on the success of these shorts, Keaton moved to full-length features. Keaton's writers included Clyde Bruckman and Jean Havez, but the most ingenious gags were often conceived by Keaton himself. The more adventurous ideas called for dangerous stunts, also performed by Keaton at great physical risk. During the railroad water-tank scene in Sherlock Jr., Keaton broke his neck when he fell against a railroad track, but did not realize it until years afterward. A scene from Steamboat Bill Jr. required Keaton to run into the shot and stand still on a particular spot. Then, the facade of a two-story building toppled forward on top of Keaton. Keaton's character emerged unscathed, thanks to a single open window which passed directly over him. The stunt required precision, because the prop house weighed two tons, and the window only offered a few inches of space around Keaton's body. The sequence became one of the iconic images of Keaton's career.

Aside from Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928), Keaton's most enduring feature-length films include Our Hospitality (1923), The Navigator (1924), Sherlock Jr. (1924), Seven Chances (1925), The Cameraman (1928), and The General (1927). The General, set during the American Civil War, combined physical comedy with Keaton's love of trains, including an epic locomotive chase. Employing picturesque locations, the film's storyline reenacted an actual wartime incident. Though it would come to be regarded as Keaton's proudest achievement, the film received mixed reviews at the time. It was too dramatic for some moviegoers expecting a lightweight comedy, and reviewers questioned Keaton's judgment in making a comedic film about the Civil War, even while noting it had a "few laughs". The fact that the heroes of the story were from the Confederate side may have also contributed to the film's unpopularity.

It was an expensive misfire, and Keaton was never entrusted with total control over his movies again. His distributor, United Artists, insisted on a production manager who monitored expenses and interfered with certain story elements. Keaton endured this treatment for two more feature films, and then exchanged his independent setup for employment at Hollywood's biggest studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Keaton's loss of independence as a filmmaker coincided with the coming of sound films (although he was interested in making the transition) and mounting personal problems, and his career in the early sound era was hurt as a result.

PART 3:SPOTLIGHT ON BUSTER KEATON: THE LATER YEARS

No comments:

Post a Comment