Cabin In The Sky marked Vincente Minnelli's feature film debut as a director and he certainly started on a grand scale. Louis B. Mayer was purportedly reluctant to do black cast feature film with an A Budget, but Minnelli and Arthur Freed's faith in Minnelli paid off big time.

Cabin In The Sky, musical fantasy, with score by John LaTouche and Vernon Duke ran for 156 performances in the 1940-1941 Broadway season. The only two members of the cast who made it to the screen version was lead Ethel Waters and Rex Ingram as Lucifer, Jr. Unless of course you count the Hall Johnson Choir.

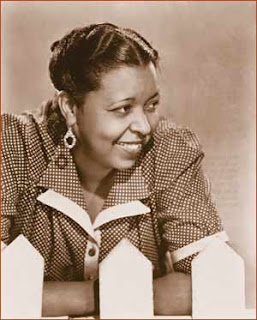

It would have never been made if MGM could not get Ethel Waters to repeat her role as the wise and faithful Petunia Johnson praying ever so that her husband Little Joe Johnson gets saved from his evil ways of drinking and gambling and carousing with that no good Georgia Brown on whom no gal made has got a shade. Come to think of it, that song should have been interpolated in the score, MGM should have paid any price for it.

MGM got their work out of Ethel though. She appeared in Cairo with Jeanette MacDonald and Robert Young and the contrasting styles of MacDonald and Waters is something to see in that film.

On Broadway Little Joe's part was played by someone who would make a big splash in Hollywood this same year of 1943. Because Dooley Wilson was playing piano at Rick's place in Casablanca, I guess he missed repeating his role. Stepping in for Wilson was America's most well known butler, Eddie 'Rochester' Anderson who did the impossible, get rich working for Jack Benny.

Sweet Georgia Brown was played by Lena Horne, the devil had no better temptress ever on screen, not even Gwen Verdon in Damn Yankees. She does a mean version of Honey In The Honeycomb.

The plot's a simple one. Petunia brings her husband Little Joe to church for the hundred and umpteenth time to get himself saved, but he slips away for a crap game and gets himself shot in the process. He's about to enter the devil's domain, but Petunia's prayers get him a six month stay of his sentence to see if he can mend his ways. After that both heavenly and hellish forces work overtime to have claim to his soul.

LaTouche and Duke gave Ethel Waters two of her best known numbers to sing, the title song and Taking A Chance On Love. Cabin In The Sky has a unique distinction of being one of the few Broadway musicals that came to the screen. Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg wrote some new material including a song for Eddie Anderson Life's Full of Consequences and another song uniquely identified with Ethel Waters, Happiness Is Just A Thing Called Joe.

Louis Armstrong is in Cabin In The Sky as Lucifer's Trumpeter and while we get a couple of licks from Satchmo, I do so wish that someone at MGM would have given him a number for himself. He doesn't standout as he usually does because of that.

Still Cabin In The Sky is a delightful film, a real treat with some of the best talent in the human race in it...

Bruce's rating: 9 out of 10