I came along too late for the Mickey Mouse club. I never have been a fan of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse as a whole yesterday. However, I had a record in my collection called "The Night That Rock N Roll Died" by a little known singer by the name of Judy Harriet. I did some research and she was a member of the Mickey Mouse Club, and of course I had to find out more.

Born Judy Harriet Spiegelman in Los Angeles in 1942 she dropped her last name for performances to avoid the anti-Semitism that still lingered in the 1950's. Her parents were immigrants from Poland, who arrived in America before World War II. Judy's early training was in classical piano and voice, and just prior to the show she had a recital at Carnegie Hall.

She performed for radio, did amateur and variety shows for television, and had released at least one 78rpm recording for Tops records prior to the show. Judy was never a straight dramatic actress, and was not particularly known for her dancing, though she had had lessons. However, she did enjoy sports, including tennis, horseback-riding, and swimming. Judy became a Mouseketeer on the Mickey Mouse Club in 1955.

Judy at thirteen had grown (and developed) more quickly than other Mouseketeers. Even though she was only of average height, she towered over the Mouseketeer boys at that time, which may have caused the directors to put her on the Blue Team at first. Judy was thus usually only seen on Guest Star Day or Circus Day. Because she seemed older and had a nice speaking voice, she was often used to introduce the guest acts, and to do comic bits with them when needed.

In 1956 she was dropped from the lineup but did a few movies. She sang "Hard Rock Candy Baby" with Judy Tyler in the movie Bop Girl Goes Calypso. In 1958 she released two 45 rpm singles, "Tall Paul/'Nuff Said", and "La Paloma/Espana" on the Surf label. (Annette had hit with "Tall Paul" though). In 1959 she recorded "Just A Guy To Love Me/I Cried For The Last Time", also on Surf.

Also that year she sang "The Night Rock 'n' Roll Died" in the Bing Crosby and Debbie Reynolds movie, Say One For Me. The movie was horrible but the soundtrack is memorable. Later that year, she co-wrote "I Promise You" with Bruce Johnston (who later joined the Beach Boys) featured in the Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow. The next year she recorded "Goliath (Big Man)/The Music of Love" and "Buffalo Bop/Restless Doll" for American International Records in 1960. She also released "Waiting for Joe/She's Got Everything" and "Road to Nowhere/Don't" on Columbia.

Between 1959 and 1964 Judy was in demand as a singer for live performances on the teenage show circuit, at civic events, and at military bases. At one such concert at Schofield Barracks on Oahu she was mobbed by 10,000 cheering GI's, and only escaped through the help of a dozen MP's. She was frequently in the fan magazines, and for a time was a member of the 'Teen Magazine variety troupe that also included the Addrisi Brothers, Tommy Cole, Roberta Shore and the Steiner Brothers. She was also visible on the party scene, dating quite a few television stars, but wasn't linked to any serious romances.

In the early sixties Judy released two more 45's thru Columbia, with the songs Waiting for Joe / She's Got Everything and Road to Nowhere / Don't. Judy stopped performing in 1964 after marrying Tony Richman, with whom she has had two daughters. She took part in the Mouseketeer reunion at Disneyland in 1975, and in the television special for the 25th Anniversary in 1980. For the last thrity years she has pretty much stayed away from the limelight. Now 70 years old, she has removed herself from Disney and her teenage years as much as she could, and I don't blame her...

Friday, June 28, 2013

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

GUEST REVIEW: RHYTHM ON THE RANGE

Another source of recording material for Bing Crosby were western songs. He recorded a good many of them in his career. About the time Rhythm on the Range was being made the singing cowboy was just getting started as a movie staple. When Bing's 78s were being compiled into vinyl albums in the 1950s he had recorded enough for several albums. Lots of the songs of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers are in the Crosby catalog in fact a young Roy Rogers can be spotted in the I'm An Old Cowhand number.

Runaway heiresses were another movie staple especially in the 1930s and that's Frances Farmer's part. She's running away from a marriage she's not terribly thrilled about and stowing away on a freight boxcar she finds Bing Crosby who unbeknownst to her works as a ranchhand on her aunt's Frying Pan Ranch out in Arizona. Bing is nursemaiding a bull named Cuddles and Bing, Frances and Cuddles make their way west with several adventures. Trailing them are a trio of hoboes played very well by James Burke, Warren Hymer, and George E. Stone who have found out who Frances is and are looking to make a quick buck. Their machinations go for naught of course. In Frances Farmer's book, Will There Ever Be A Morning, she describes a not very happy life in Hollywood. However she liked this film, as it had no pretensions and similarly her leading man. She described Bing Crosby as a pleasant unassuming fellow who she liked, but didn't get to know real well. Frances had a best friend, a matron of honor to be, for the wedding that didn't come off. She was played by Martha Sleeper and I think a lot of her part was edited out. Sleeper gave some hints of a really juicy Eve Arden type character that could have been used more.

The second leads were played by Bob Burns and Martha Raye. Burns, the Arkansas Traveler and regular on Crosby's Kraft Music Hall, played his usual rustic type and in this film introduced his patented musical instrument, the bazooka. Made out of two gas pipes and a funnel, the bazooka was a kind of countrified bassoon. The army's anti-tank device in World War II looked something like it and it was named as such. Martha Raye made her debut in this film and would go on to do two other films with Crosby. She sings her famous Mr. Paganini number here and her bumptious character complement Burns quite nicely. Crosby sings A Cowboy's Lullaby to Cuddles trying to calm him down during the train ride and the famous Empty Saddles during a scene at the Madison Square Garden Rodeo. He gets a ballad entitled I Can't Escape From You to sing while on the road with Farmer.

The most famous song to come out of this film is I'm An Old Cowhand which was a big seller for him. It's an ensemble number with just about everyone in the cast participating including as I said before, Roy Rogers and also a young Louis Prima. Now there's an interesting combination. I'm An Old Cowhand was written with words and music by Crosby's good friend and sometime singing partner Johnny Mercer. IT's a good film and I'm surprised Paramount didn't come up with any more Western type material for Bing considering he did a lot of recording of that material. The only other western type ballads he ever sung on the screen were The Funny Old Hills from Paris Honeymoon and When The Moon Comes Over Madison Square from Rhythm on the River. Crosby would have to wait until he essayed Thomas Mitchell's part in the remake of Stagecoach during the 1960s to be in another western. And there he sang no songs at all.

One song that was cut out from the film was a duet by Crosby and Farmer called The House Jack Built for Jill. Crosby did record it for Decca as a solo and it is heard towards the end of the film in background. I was lucky to get a bootleg recording from the cut soundtrack. Frances talk/sings a la Rex Harrison and Bing sings it in his inimitable style. I think this was supposed to be a finale and it was cut at the last minute. The film does end somewhat abruptly and you can tell there was more shot. Maybe one day it will be restored. Rhythm on the Range was remade by Paramount with Martin and Lewis as Pardners. Dean and Jerry are good, but it ain't a patch to the original...

Monday, June 24, 2013

MARY LIVINGSTONE: THE WOMAN BEHIND BENNY

My favorite comedian of all-time was Jack Benny. His personna of being a cheapskate, forever 39, and a bachelor was nothing further from the truth. Not only was he generous, but he always was married for many years to one woman - who was his partner on and off the stage. Mary Livingstone, born Sadie Marks on June 23, 1905, was an American radio comedienne and the wife and radio partner of comedy great Jack Benny. Enlisted almost entirely by accident to perform on her husband's popular program, she proved a talented comedienne. But she also proved one of the rare performers – Barbra Streisand would prove to be another – to experience severe stage fright years after her career was established — so much so that she retired from show business completely, after two decades in the public eye, almost three decades before her death, and at the height of her husband and partner's fame.

Born in Seattle, but raised in Vancouver, British Columbia, Livingstone's father was a Jewish immigrant from Romania. She came from a family of merchants and traders who had worked their way across Canada. She met her future husband, Jack Benny, at a Passover seder at her family home when she was 14; Benny was invited by his friend Zeppo (b. Herbert) Marx while Benny and the Marx Brothers were in town together to perform. Sadie developed a near-instant crush on the funny, somewhat shy man eleven years her senior. But when he inadvertently insulted her by excusing himself for the night in the midst of her violin performance, she got her revenge the next night. She took three girlfriends to the theater where Benny performed, sitting in the front row and making sure not to laugh. Benny said later it drove him nuts that he couldn't get the four girls to laugh at anything.

Three years later, aged 17, Sadie visited California with her family while Jack Benny was in the same town for a show. Still nursing a small crush on the comedian, Sadie went to the theater to re-introduce herself to him. As he approached her in a hallway, she smiled and said, "Hello, Mr. Benny, I'm..." But he curtly cut her off with a "Hello," and continued on his way down the hall without pausing; she learned much later that when Benny was deep in thought about his work, it was nearly impossible to get his attention otherwise.

They met again a few years later — while she was said to be working as a lingerie salesgirl at a May Department Stores branch store in downtown Los Angeles — and the couple finally began dating. Invited on a double-date by a friend who had married Sadie's sister, Babe, Benny brought Sadie along to keep him company. This time, the couple clicked: Jack was finally smitten with Sadie and asked her on another date. She turned him down at first — she was seeing another young man — but Benny persisted. He visited her at The May Company almost daily and was reputed to buy so much ladies' hosiery from her he helped her set a sales record; he also called her several times a day when on the road.

As part of Benny's vaudeville act; she was still known as Sadie at the timeSadie took part in some of Jack's vaudeville performances but never thought of herself as a full-time performer, seeming glad to be done with it when he moved to radio in 1932. Then came the day he called her at home and asked her to come to the studio quickly. An actress hired to play a part on the evening's show didn't show up and, instead of risking a hunt for a substitute, Benny thought his wife could handle the part: a character named "Mary Livingstone" scripted as Benny's biggest fan.

At first, it seemed like a brief role — she played the part on that night's and the following week's show before being written out of the scenario. But NBC received so much fan mail that the character was revived into a regular feature on the Benny show, and the reluctant Sadie Marks became a radio star in her own right. Mary Livingstone underwent a change, too: from fan to tart secretary-foil; the character occasionally went on dates with Benny's character but they were rarely implied to be truly romantically involved otherwise. The lone known exceptions were a fantasy sequence used on both the radio and television versions of the show, as well as during an NBC musical tribute to Benny, in which Mary admitted to being "Mrs. Benny."

Livingstone soon enough displayed her own sharp wit and pinpoint comic timing, often used to puncture Benny's on-air ego, and she became a major part of the show, enough so that, giving in when she was addressed as "Mary Livingstone" often enough when out in public, she ended up changing her name legally to Mary Livingstone. Years later, her husband admitted how strange it felt to call her Sadie, even in private. They would also adopt a girl named Joan in 1939. Joan was always close to her father, but unfortunately did not have the same closeness with her mother.

Mary's trademark bit on the radio show, other than haranguing Benny, was to read letters from her mother (who lived in Plainfield, New Jersey), usually beginning with, My darling daughter Mary... and often including comical stories about Mary's (fictional) sister Babe – similar to Sadie's real sister Babe in name only – who was so masculine she played as a linebacker for the Green Bay Packers and worked in steel mills and coal mines; or, their ne'er-do-well father, who always seemed to be a half-step ahead of the law. Mother Livingstone, naturally enough, detested Benny and was forever advising her daughter to quit his employ.

Never all that comfortable as a performer despite her success, Livingstone's stage fright became so acute by the time the Benny show was moving toward television that she rarely appeared on the radio show in its final season, 1954-55. When she did appear, the Bennys' adopted daughter, Joan, occasionally acted as a stand-in for her mother; or Mary's lines were read in rehearsals by Jack's script secretary, Jeanette Eyman, while Livingstone's pre-recorded lines were played during live broadcasts. Livingstone made few appearances on the television version – mostly in filmed episodes – and finally retired from show business after her close friend Gracie Allen did in 1958.

George Burns revealed in his memoir Gracie: A Love Story (1988) that he and his wife and performing partner Gracie Allen loved Jack Benny, but merely tolerated Mary, whom they disliked. Lucille Ball felt the same way, referring to Mary as a "hard-hearted Hannah". Livingstone's relationship with their adopted daughter, Joan, was strained. In Sunday Nights at Seven (1990), her father's unfinished memoir that she completed with her own recollections, Joan Benny revealed she rarely felt close to her mother, and the two often argued.

Mary Livingstone's brother, Hilliard Marks (1913-1982), was a radio and television producer who worked primarily for his brother-in-law Jack Benny. After writing a biography of her husband, Mary Livingstone — whose surname is often misspelled without the 'e', as with her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contribution to radio — died from cardiovascular disease at her home in Holmby Hills, California on June 30, 1983, aged 78, hours after receiving a visit from then-First Lady Nancy Reagan, as daughter Joan noted, where the two women enjoyed a private manicure appointment, and seven days after her 78th birthday. "The doctor said it was a heart attack", Joan wrote, "but I have always felt she just gradually faded out of life."

Mary Livingstone is interred beside her husband in the Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. After Jack Benny died on Christmas Day 1974, he had Mary sent a rose every day for the rest of her life. In those years, it was estimated that Mary received 3200 roses. Mary Livingstone was truly the woman behind the man, no matter what her flaws...

Born in Seattle, but raised in Vancouver, British Columbia, Livingstone's father was a Jewish immigrant from Romania. She came from a family of merchants and traders who had worked their way across Canada. She met her future husband, Jack Benny, at a Passover seder at her family home when she was 14; Benny was invited by his friend Zeppo (b. Herbert) Marx while Benny and the Marx Brothers were in town together to perform. Sadie developed a near-instant crush on the funny, somewhat shy man eleven years her senior. But when he inadvertently insulted her by excusing himself for the night in the midst of her violin performance, she got her revenge the next night. She took three girlfriends to the theater where Benny performed, sitting in the front row and making sure not to laugh. Benny said later it drove him nuts that he couldn't get the four girls to laugh at anything.

Three years later, aged 17, Sadie visited California with her family while Jack Benny was in the same town for a show. Still nursing a small crush on the comedian, Sadie went to the theater to re-introduce herself to him. As he approached her in a hallway, she smiled and said, "Hello, Mr. Benny, I'm..." But he curtly cut her off with a "Hello," and continued on his way down the hall without pausing; she learned much later that when Benny was deep in thought about his work, it was nearly impossible to get his attention otherwise.

They met again a few years later — while she was said to be working as a lingerie salesgirl at a May Department Stores branch store in downtown Los Angeles — and the couple finally began dating. Invited on a double-date by a friend who had married Sadie's sister, Babe, Benny brought Sadie along to keep him company. This time, the couple clicked: Jack was finally smitten with Sadie and asked her on another date. She turned him down at first — she was seeing another young man — but Benny persisted. He visited her at The May Company almost daily and was reputed to buy so much ladies' hosiery from her he helped her set a sales record; he also called her several times a day when on the road.

As part of Benny's vaudeville act; she was still known as Sadie at the timeSadie took part in some of Jack's vaudeville performances but never thought of herself as a full-time performer, seeming glad to be done with it when he moved to radio in 1932. Then came the day he called her at home and asked her to come to the studio quickly. An actress hired to play a part on the evening's show didn't show up and, instead of risking a hunt for a substitute, Benny thought his wife could handle the part: a character named "Mary Livingstone" scripted as Benny's biggest fan.

At first, it seemed like a brief role — she played the part on that night's and the following week's show before being written out of the scenario. But NBC received so much fan mail that the character was revived into a regular feature on the Benny show, and the reluctant Sadie Marks became a radio star in her own right. Mary Livingstone underwent a change, too: from fan to tart secretary-foil; the character occasionally went on dates with Benny's character but they were rarely implied to be truly romantically involved otherwise. The lone known exceptions were a fantasy sequence used on both the radio and television versions of the show, as well as during an NBC musical tribute to Benny, in which Mary admitted to being "Mrs. Benny."

Livingstone soon enough displayed her own sharp wit and pinpoint comic timing, often used to puncture Benny's on-air ego, and she became a major part of the show, enough so that, giving in when she was addressed as "Mary Livingstone" often enough when out in public, she ended up changing her name legally to Mary Livingstone. Years later, her husband admitted how strange it felt to call her Sadie, even in private. They would also adopt a girl named Joan in 1939. Joan was always close to her father, but unfortunately did not have the same closeness with her mother.

Mary's trademark bit on the radio show, other than haranguing Benny, was to read letters from her mother (who lived in Plainfield, New Jersey), usually beginning with, My darling daughter Mary... and often including comical stories about Mary's (fictional) sister Babe – similar to Sadie's real sister Babe in name only – who was so masculine she played as a linebacker for the Green Bay Packers and worked in steel mills and coal mines; or, their ne'er-do-well father, who always seemed to be a half-step ahead of the law. Mother Livingstone, naturally enough, detested Benny and was forever advising her daughter to quit his employ.

Never all that comfortable as a performer despite her success, Livingstone's stage fright became so acute by the time the Benny show was moving toward television that she rarely appeared on the radio show in its final season, 1954-55. When she did appear, the Bennys' adopted daughter, Joan, occasionally acted as a stand-in for her mother; or Mary's lines were read in rehearsals by Jack's script secretary, Jeanette Eyman, while Livingstone's pre-recorded lines were played during live broadcasts. Livingstone made few appearances on the television version – mostly in filmed episodes – and finally retired from show business after her close friend Gracie Allen did in 1958.

George Burns revealed in his memoir Gracie: A Love Story (1988) that he and his wife and performing partner Gracie Allen loved Jack Benny, but merely tolerated Mary, whom they disliked. Lucille Ball felt the same way, referring to Mary as a "hard-hearted Hannah". Livingstone's relationship with their adopted daughter, Joan, was strained. In Sunday Nights at Seven (1990), her father's unfinished memoir that she completed with her own recollections, Joan Benny revealed she rarely felt close to her mother, and the two often argued.

Mary Livingstone's brother, Hilliard Marks (1913-1982), was a radio and television producer who worked primarily for his brother-in-law Jack Benny. After writing a biography of her husband, Mary Livingstone — whose surname is often misspelled without the 'e', as with her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for her contribution to radio — died from cardiovascular disease at her home in Holmby Hills, California on June 30, 1983, aged 78, hours after receiving a visit from then-First Lady Nancy Reagan, as daughter Joan noted, where the two women enjoyed a private manicure appointment, and seven days after her 78th birthday. "The doctor said it was a heart attack", Joan wrote, "but I have always felt she just gradually faded out of life."

Mary Livingstone is interred beside her husband in the Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery in Culver City, California. After Jack Benny died on Christmas Day 1974, he had Mary sent a rose every day for the rest of her life. In those years, it was estimated that Mary received 3200 roses. Mary Livingstone was truly the woman behind the man, no matter what her flaws...

Friday, June 21, 2013

STAR FRIENDS: LUCILLE BALL AND CAROL BURNETT

Lucille Ball was and is an icon among the pioneers of television. She starred on television in three sitcoms from 1951 to 1974, and her trail blazing sitcom "I Love Lucy" is reported played someone in the world every minute. Ball, to me, was more of an actress doing comedy than an actual comedic funny woman, but she did have great timing needed to get laughs. Ball was also good friends with a true comedic genius, Carol Burnett, and they became friends early in Carol's career.

“[Lucy] came to see me the second night of an off-Broadway show I was doing in 1958 — I was 25, and she was in the audience… I peeked out of the curtain and I saw this carrot-top in the second row and I thought I was going to die,” Carol remembered. “I was more nervous that night than I was the night before, when we opened with all the critics, because it was Lucy!

“I got through the show and then she came backstage and she called me ‘kid,’” Carol continued. “‘Kid, you were really terrific.’ She was very encouraging and she said, ‘If ever you need me for anything, kid, give me a call. I’ll be there.’”

Carol took Lucy up on her offer several years later when she was offered a special on CBS on the condition that she find a “big star” to guest star with her. After much prompting from her producer, Carol agreed to phone the “I Love Lucy” star.

“They talked me into picking up the phone and calling her and she took the call right away and said, ‘Hi kid, how are you? What’s going on?’” she told Billy and Kit. “I said, ‘Lucy, I know you’re busy, I don’t want to bother you, but they were asking me to call… I’m doing this television show special with CBS--’ and she said, ‘I’ll be there. When do you want me there?’ And that was it.”

The redheaded comedy dream team became close and remained friends until Lucy’s death.

“Every year on my birthday, [Lucy] would send me flowers and she gave me my baby shower for my second baby,” Carol told Billy and Kit. “She was on my show several times and I guest [starred] on hers, so we were really close.”

Lucille Ball died on April 26, 1989 at the age of 77. Burnett added, “She died on my birthday. I remember getting up and seeing it on the morning shows and it was out of the blue. She’d been sick, but they thought she was going to come home and she died. I got my flowers [from her] that afternoon."

Recently, Carol Burnett called the executive director of the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Center in Ball’s hometown to ask, “How can I help?” Executive director Ric Wyman reported, “Naturally, my first response was to invite her to Jamestown, New York. While Ms. Burnett agreed that she hopes to be able to visit here some day, she was more immediately able to provide us with something we’ve wanted for a long time.”

As a result, her hometown museum now holds in its archives a copy of every installment of The Carol Burnett Show in which Lucille Ball appeared...

SOURCE

“[Lucy] came to see me the second night of an off-Broadway show I was doing in 1958 — I was 25, and she was in the audience… I peeked out of the curtain and I saw this carrot-top in the second row and I thought I was going to die,” Carol remembered. “I was more nervous that night than I was the night before, when we opened with all the critics, because it was Lucy!

“I got through the show and then she came backstage and she called me ‘kid,’” Carol continued. “‘Kid, you were really terrific.’ She was very encouraging and she said, ‘If ever you need me for anything, kid, give me a call. I’ll be there.’”

Carol took Lucy up on her offer several years later when she was offered a special on CBS on the condition that she find a “big star” to guest star with her. After much prompting from her producer, Carol agreed to phone the “I Love Lucy” star.

“They talked me into picking up the phone and calling her and she took the call right away and said, ‘Hi kid, how are you? What’s going on?’” she told Billy and Kit. “I said, ‘Lucy, I know you’re busy, I don’t want to bother you, but they were asking me to call… I’m doing this television show special with CBS--’ and she said, ‘I’ll be there. When do you want me there?’ And that was it.”

The redheaded comedy dream team became close and remained friends until Lucy’s death.

“Every year on my birthday, [Lucy] would send me flowers and she gave me my baby shower for my second baby,” Carol told Billy and Kit. “She was on my show several times and I guest [starred] on hers, so we were really close.”

Lucille Ball died on April 26, 1989 at the age of 77. Burnett added, “She died on my birthday. I remember getting up and seeing it on the morning shows and it was out of the blue. She’d been sick, but they thought she was going to come home and she died. I got my flowers [from her] that afternoon."

Recently, Carol Burnett called the executive director of the Lucille Ball-Desi Arnaz Center in Ball’s hometown to ask, “How can I help?” Executive director Ric Wyman reported, “Naturally, my first response was to invite her to Jamestown, New York. While Ms. Burnett agreed that she hopes to be able to visit here some day, she was more immediately able to provide us with something we’ve wanted for a long time.”

As a result, her hometown museum now holds in its archives a copy of every installment of The Carol Burnett Show in which Lucille Ball appeared...

SOURCE

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

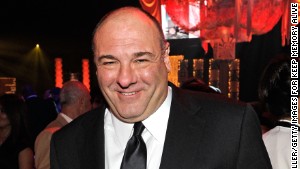

RIP: JAMES GANDOLFINI

Tony Soprano is dead. Shocking news is rippling through the world of entertainment. Actor James Gandolfini has died. James Gandolfini, best known for his role as an anxiety-ridden mob boss on HBO's "The Sopranos," died in Italy, possibly of a heart attack, the actor's managers said Wednesday. He was 51.

"It is with immense sorrow that we report our client, James Gandolfini. passed away today while on holiday in Rome, Italy," managers Mark Armstrong and Nancy Sanders said in a joint statement. "Our hearts are shattered and we will miss him deeply. He and his family were part of our family for many years and we are all grieving." The actor had been scheduled to make an appearance at the Taormina Film Fest in Sicily this week.

Gandolfini won three Emmy Awards for his portrayal of Tony Soprano, the angst-ridden mob boss who visited a therapist and took Prozac while knocking off people. "The Sopranos" aired from 1999 to 2007.

Gandolfini was born September 18, 1961, in Westwood, New Jersey ,and he graduated from Rutgers University and, as the story goes, worked as a bartender and a bouncer in New York City until he went with a friend to an acting class. He got his start on Broadway, with a role in the 1992 revival of "A Streetcar Named Desire" with Jessica Lange and Alec Baldwin. Gandolfini's big screen debut came in the role of a heavy in the bloody "True Romance" in 1993. His breakthrough on the small screen came in 1999 with the role of Tony Soprano.

Gandolfini's acting credits included roles in "The Last Castle" with Robert Redford, "The Mexican" with Brad Pitt and Julia Roberts and "Surviving Christmas" with Ben Affleck. In recent years, he had starred in several movies, including the Oscar-nominated "Zero Dark Thirty," "The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3" and "Killing Them Softly."

Gandolfini is survived by his wife, Deborah, and their 9-month-old daughter, Liliana. He is also survived by a son, Michael, from another marriage...

GENE WILDER AT 80

Gene Wilder doesn't think he's funny -- at least not in real life.

"[People] say, 'What a comic, what a funny guy,' and I'm not -- I am really not -- except in a comedy film," said the actor, who made a rare public appearance Thursday night (June 13) at the 92Y in New York City. "I also make my wife laugh once or twice in the house, but nothing special."

It's a bit odd to hear Wilder, known for playing comedic roles in films, including "Blazing Saddles," "The Producers," and "Young Frankenstein," to say something like this. Then again, Wilder always was a dramatic actor at heart, studying at renown institutions the Old Vic, in England, and Lee Strasberg's Actors Studio, in New York, before earning acclaim in his now classic comedies.

Last night, Wilder spoke about his career in and outside of show business, with Turner Classic Movies host Robert Osbourne. The actor touched on everything from his early acting days to his roles in movies like "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" to why he hasn't appeared on-screen in more than 20 years, opting instead to write books.

"I like writing books," said Wilder, who is about to release his second novel, "Something to Remember You By." "I'd rather be at home with my wife. I can write, take a break, come out, have a glass of tea, give my wife a kiss, and go back in and write some more. It's not so bad. I am really lucky."

Before he became an author and celebrated actor, Wilder began his professional career in 1966, with a supporting role in the TV adaptation of Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman." One year later, he appeared in the crime drama "Bonnie and Clyde" as Eugene Gizzard. While that movie went on to become an American classic, it was an encounter he had soon after that that would help launch his career.

After that, Brooks cast Wilder as Leo Bloom in "The Producers," a role that ended up securing him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Wilder would work with Brooks again six years later, on the Western comedy "Blazing Saddles," and then a third time, on "Young Frankenstein." For "Saddles," Wilder played the gunslinger Jim, or "The Waco Kid." However, that wasn't the original plan.

"Saddles" marked another important turn in Wilder's career, as it was the first time he worked with Richard Pryor, who co-wrote the film. Wilder would go on to star in four movies with the comedian: "Silver Streak," "Stir Crazy," "See No Evil, Hear No Evil," and "Another You." The on-screen chemistry between the two actors was palpable. However, Pryor's drug habit off-screen made things difficult.

"'Silver Streak' was very good, we got along really swell. But when we did 'Stir Crazy,' he'd come in 15 minutes late, 30 minutes late, 45 minutes late, an hour late. [Director] Sidney [Poitier] was going nuts," Wilder said.

Unfortunately, by the late '80s, Pryor's health was in rapid decline, which was very difficult for his friend and co-star to watch.

"He had a heart [issue], and he wanted to smoke. The doctor said, 'I am telling you, if you smoke, you will die. Don't smoke.' When I went to see him, he had cigarettes and a lighter, and he couldn't walk without stumbling. He couldn't really do much, except he knew how to put the cigarette in his mouth. I didn't know what I could say to him to stop him from smoking cigarettes."

"Another You," which Wilder also starred in with Pryor, was the final movie in which Wilder appeared; his last three credits are all TV movies: "Murder in a Small Town," "Alice in Wonderland," and "The Lady in Question."

So what made him leave acting? As Wilder has previously explained, he wasn't interested in the way in which films were headed. At the 92Y, he elaborated on this -- and even left open the possibility of acting once again.

"After a while, [films] were so dirty. Once in awhile, there was a nice, good film, but not very many," Wilder said. "If something comes along and it's really good and I think I'd be good for it, I'd be happy to do it. Not too many came along. I mean, they came along, but I didn't want to do them. I didn't want to do 3D, for instance. I didn't want to do ones that were just bombing and swearing. If someone says 'Ah, go f*ck yourself,' if it came from a meaningful place, I'd understand it. But if you go to some movies, can't they just stop and talk once in awhile?"

Since Wilder seems open to it, perhaps it's time that someone came and wrote a part just for him -- one that doesn't involve unnecessary swearing, explosions, or 3D, of course. Also, it probably shouldn't be a remake, either, a trend Wilder seems less than impressed with. Take, for instance, the 2005 version of "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory." Wilder, of course, is best known for portraying chocolatier Willy Wonka in Mel Stuart's "Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory." But he did not mince words about Tim Burton's take on the beloved Roald Dahl tale.

"I think it's an insult. It's probably Warner Bros.' insult," Wilder said. "Johnny Depp, I think, is a good actor, but I don't care for that director. He's a talented man, but I don't care for him doing stuff like he did."

If you consider the types of films Hollywood is putting out now, it might be tough for Wilder to find the right part. Then again, he seems content on what he's doing now. In fact, earlier in the evening, Robert Osbourne had asked Wilder about his thoughts on working in Hollywood. Not surprisingly, his immediate reply was "Yuck! I don't like it."

SOURCE

UPDATE: UNFORTUNATELY, GENE WILDER DIED ON AUGUST 28TH, 2016 AT THE AGE OF 83. YOU CAN READ MORE ABOUT IT HERE

Monday, June 17, 2013

BORN ON THIS DAY: RALPH BELLAMY

I have to admit that even though I try to see every classic movie I have the opportunity or time to watch that there are a few stars that slip through my viewings. One of those stars is birthday boy Ralph Bellamy. I have seen him as the man trying to steal Ginger Rogers from Fred Astaire in Carefree (1938), and of course I have seen him as the millionaire tycoon in Eddie Murphy's Trading Places (1983), but that is about it. After researching this article, I think I am due to watch more of his films.

He was born Ralph Rexford Bellamy in Chicago, Illinois on June 17, 1904, the son of Lilla Louise (née Smith), a native of Canada, and Charles Rexford Bellamy. He ran away from home when he was fifteen and managed to get into a road show. He toured with road shows before finally landing in New York City, New York. He began acting on stage there and by 1927 owned his own theatre company. In 1931, he made his film debut and worked constantly throughout the decade first as a lead then as a capable supporting actor. Bellamy was cast in the lead role in the film Straight from the Shoulder (1936) and also in the film It Can't Last Forever (1937) with Edward J. Pawley.

Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell and Bellamy in a publicity shot for His Girl Friday (1940). He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in The Awful Truth (1937) with Irene Dunne and Cary Grant, and played a similar part, that of a naive boyfriend competing with the sophisticated Grant character, in His Girl Friday (1940). He portrayed detective Ellery Queen in a few films during the 1940s, but as his film career did not progress, he returned to the stage, where he continued to perform throughout the fifties. Highly regarded within the industry, he was a founder of the Screen Actors Guild and served as President of Actors' Equity from 1952-1964.

He appeared on Broadway in one of his most famous roles, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Sunrise at Campobello. He later starred in the 1960 film version. In the summer of 1961, Bellamy hosted nine original episodes of a CBS Western anthology series called Frontier Justice, a Dick Powell Four Star Television production.

On film, he also starred in the Western The Professionals (1966) as an oil tycoon opposite adventurers Burt Lancaster and Lee Marvin, and Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968) as an evil physician, before turning to television during the 1970s. An Emmy Award nomination for the mini-series The Winds of War (1983) – in which Bellamy reprised his Sunrise at Campobello role of Franklin Roosevelt – brought him back into the spotlight. This was quickly followed by his role as Randolph Duke, a conniving billionaire commodities trader in Trading Places (1983), alongside Don Ameche. The 1988 Eddie Murphy film, Coming to America, included a brief cameo by Bellamy and Don Ameche, reprising their roles as the Duke brothers. In 1988 he again portrayed Franklin Roosevelt in the sequel to The Winds of War, War and Remembrance. Among his later roles was a memorable appearance as a once-brilliant but increasingly forgetful lawyer sadly skewered by the Jimmy Smits character on an episode of L.A. Law. He continued working regularly and gave his final performance in Pretty Woman (1990).

Married four times, Bellamy died on November 29, 1991, at Saint John's Health Center in Santa Monica, California, from a lung ailment. He was 87 years old....

He was born Ralph Rexford Bellamy in Chicago, Illinois on June 17, 1904, the son of Lilla Louise (née Smith), a native of Canada, and Charles Rexford Bellamy. He ran away from home when he was fifteen and managed to get into a road show. He toured with road shows before finally landing in New York City, New York. He began acting on stage there and by 1927 owned his own theatre company. In 1931, he made his film debut and worked constantly throughout the decade first as a lead then as a capable supporting actor. Bellamy was cast in the lead role in the film Straight from the Shoulder (1936) and also in the film It Can't Last Forever (1937) with Edward J. Pawley.

Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell and Bellamy in a publicity shot for His Girl Friday (1940). He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in The Awful Truth (1937) with Irene Dunne and Cary Grant, and played a similar part, that of a naive boyfriend competing with the sophisticated Grant character, in His Girl Friday (1940). He portrayed detective Ellery Queen in a few films during the 1940s, but as his film career did not progress, he returned to the stage, where he continued to perform throughout the fifties. Highly regarded within the industry, he was a founder of the Screen Actors Guild and served as President of Actors' Equity from 1952-1964.

He appeared on Broadway in one of his most famous roles, as Franklin Delano Roosevelt in Sunrise at Campobello. He later starred in the 1960 film version. In the summer of 1961, Bellamy hosted nine original episodes of a CBS Western anthology series called Frontier Justice, a Dick Powell Four Star Television production.

On film, he also starred in the Western The Professionals (1966) as an oil tycoon opposite adventurers Burt Lancaster and Lee Marvin, and Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968) as an evil physician, before turning to television during the 1970s. An Emmy Award nomination for the mini-series The Winds of War (1983) – in which Bellamy reprised his Sunrise at Campobello role of Franklin Roosevelt – brought him back into the spotlight. This was quickly followed by his role as Randolph Duke, a conniving billionaire commodities trader in Trading Places (1983), alongside Don Ameche. The 1988 Eddie Murphy film, Coming to America, included a brief cameo by Bellamy and Don Ameche, reprising their roles as the Duke brothers. In 1988 he again portrayed Franklin Roosevelt in the sequel to The Winds of War, War and Remembrance. Among his later roles was a memorable appearance as a once-brilliant but increasingly forgetful lawyer sadly skewered by the Jimmy Smits character on an episode of L.A. Law. He continued working regularly and gave his final performance in Pretty Woman (1990).

Married four times, Bellamy died on November 29, 1991, at Saint John's Health Center in Santa Monica, California, from a lung ailment. He was 87 years old....

Friday, June 14, 2013

PHOTOS OF THE DAY: STARS AND THEIR FATHERS

Behind every great Hollywood star was probably a show business parent or two. To commemorate Father's Day, I wanted to put together some interesting pictures of classic Hollywood stars and their dear old dads. I was surprised to discover that it was harder to find classic Hollywood stars and their fathers than it was to find their mothers. I guess there are more stage mothers than stage fathers...

|

| SHIRLEY TEMPLE AND HER FATHER |

|

| MICKEY ROONEY AND HIS FATHER |

|

| RITA HAYWORTH AND HER FATHER |

|

| ELIZABETH TAYLOR AND HER FATHER |

|

| AL JOLSON AND HIS FATHER |

|

| JERRY LEWIS WITH HIS FATHER AND HIS SON |

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

AT HOME WITH ELEANOR POWELL

Known as "The Girl from Pennsylvania Avenue", Eleanor Torrey Powell was originally born November 21, 1912, in Springfield, Mass. Her mother, wanting Eleanor to learn to overcome her shyness, placed her in dancing school when she was but 13. She studied Ballet and "Acrobatic Dancing" and was discovered by Gus Edwards dancing in Atlantic City while still a child. Edwards put her in one of his celebrated Children's Reviews. Powell caught "the bug" and set her sites on Broadway. She took 10 lessons in Tap (for $35) and made her Broadway debut in 1928. One year later her "machine-gun footwork" earned her the title "World's Greatest Feminine Tap Dancer".

In 1935 Eleanor Powell "went Hollywood" starring in George White's Scandals. Word has it she so longed for the comfort and serenity of her Crestwood lifestyle, that when MGM approached her about doing another Hollywood film, she demanded a significant increase in wages and star billing. To her surprise, she got both (!).

Eleanor Powell stayed in Hollywood through the late 1930s, making some of the greatest musicals of the era. She became known as the Queen of Tap, and starred opposite Fred Astaire and George Murphy (both in the Broadway Melody series), among other celebrated tappers, although her forte was as a soloist. She made a total of 13 films between 1935 and 1950, giving up life on the "silvery screen" with her marriage to Glenn Ford.

Her fifth film, Broadway Melody of 1938 ( in which she starred opposite Robert Taylor,) found her in the company of another noted Crestwoodian, Robert Benchley.

Powell also had a public television show called "Faith of our Children," in the 1950's based on her Sunday School Classes. Even more than her film career she loved being with children and once said "There's nothing in the word like having a child love you." After her divorce from Ford, Powell started an short but successful night-club career. Eleanor Powell died February 11th, 1982, of cancer.

Eleanor Powell called Crestwood home in the early 1930s. Some old-timers recall with fondness this down-to-earth star of stage and screen. When she was rehearsing at home, the sound of her "tapping" on her home's hardwood floors would resonate throughout the neighborhood. An amateur ornithologist, Ms. Powell could often be found birdwatching along the Bronx River at dawn...

SOURCE

Monday, June 10, 2013

WINGY MANONE: THE ONE ARMED GENIUS

I first noticed Wingy Manone in a Bing Crosby musical, and I was amazed at his ability. I did not really know much about him or his music, but the more I heard the more I enjoyed. There is not much written on Wingy Manone, and that is a shame because he was one of the truly great jazz masters. Wingy Manone was born Joseph Matthews Mannone in New Orleans, Louisiana on February 13, 1900. He lost an arm in a streetcar accident in 1910, which resulted in his nickname of "Wingy". He used a prosthesis, so naturally and unnoticeably that his disability was not apparent to the public.

After playing trumpet and cornet professionally with various bands in his home town, he began to travel across America in the 1920s, working in Chicago, New York City, Texas, Mobile, Alabama, California, St. Louis, Missouri and other locations; he continued to travel widely throughout the United States and Canada for decades.

Wingy Manone's style was similar to that of fellow New Orleans trumpeter Louis Prima: hot jazz with trumpet leads, punctuated by good-natured spoken patter in a pleasantly gravelly voice. Manone was an esteemed musician who was frequently recruited for recording sessions. He played on some early Benny Goodman records, for example, and fronted various pickup groups under pseudonyms like "The Cellar Boys" and "Barbecue Joe and His Hot Dogs." His hit records included "Tar Paper Stomp" (an original riff composition of 1929, later used as the basis for Glenn Miller's "In the Mood"), and a hot 1934 version of a sweet ballad of the time "The Isle of Capri", which was said to have annoyed the songwriters despite the royalties it earned them.\

Manone's group, like other bands, often recorded alternate versions of songs during the same sessions; Manone's vocals would be used for the American, Canadian, and British releases, and strictly instrumental versions would be intended for the international, non-English-speaking markets. Thus there is more than one version of many Wingy Manone hits. Among his better records are "There'll Come a Time (Wait and See)" (1934, also known as "San Antonio Stomp"), "Send Me" (1936), and the novelty hit "The Broken Record" (1936). He and his band did regular recording and radio work through the 1930s, and appeared with Bing Crosby in the movie Rhythm on the River in 1940.

In 1943 he recorded several tunes as "Wingy Manone and His Cats"; that same year he performed in Soundies movie musicals. One of his Soundies reprised his recent hit "Rhythm on the River."

From the 1950s he was based mostly in California and Las Vegas, Nevada, although he also toured through the United States, Canada, and parts of Europe to appear at jazz festivals. In 1957, he attempted to break into the teenage rock-and-roll market with his version of Party Doll, the Buddy Knox hit. His version on Decca 30211 made No. 56 on Billboard's Pop chart and it received a UK release on Brunswick 05655.

A lifelong friend of Bing Crosby, he appears in many of Crosby's radio shows in the 1940s and 1950s. Wingy Manone lived in Las Vegas from 1954 up until his death and he stayed active until near the end, although he only recorded one full album (for Storyville in 1966) after 1960. Wingy died on July 9th 1982 in Las Vegas. Manone was largely forgotten by that time despite performing until the end. However, his talent and his ability should not be underestimated. Wingy did more musically with one arm what most people can not do with two working arms....

After playing trumpet and cornet professionally with various bands in his home town, he began to travel across America in the 1920s, working in Chicago, New York City, Texas, Mobile, Alabama, California, St. Louis, Missouri and other locations; he continued to travel widely throughout the United States and Canada for decades.

Wingy Manone's style was similar to that of fellow New Orleans trumpeter Louis Prima: hot jazz with trumpet leads, punctuated by good-natured spoken patter in a pleasantly gravelly voice. Manone was an esteemed musician who was frequently recruited for recording sessions. He played on some early Benny Goodman records, for example, and fronted various pickup groups under pseudonyms like "The Cellar Boys" and "Barbecue Joe and His Hot Dogs." His hit records included "Tar Paper Stomp" (an original riff composition of 1929, later used as the basis for Glenn Miller's "In the Mood"), and a hot 1934 version of a sweet ballad of the time "The Isle of Capri", which was said to have annoyed the songwriters despite the royalties it earned them.\

Manone's group, like other bands, often recorded alternate versions of songs during the same sessions; Manone's vocals would be used for the American, Canadian, and British releases, and strictly instrumental versions would be intended for the international, non-English-speaking markets. Thus there is more than one version of many Wingy Manone hits. Among his better records are "There'll Come a Time (Wait and See)" (1934, also known as "San Antonio Stomp"), "Send Me" (1936), and the novelty hit "The Broken Record" (1936). He and his band did regular recording and radio work through the 1930s, and appeared with Bing Crosby in the movie Rhythm on the River in 1940.

In 1943 he recorded several tunes as "Wingy Manone and His Cats"; that same year he performed in Soundies movie musicals. One of his Soundies reprised his recent hit "Rhythm on the River."

From the 1950s he was based mostly in California and Las Vegas, Nevada, although he also toured through the United States, Canada, and parts of Europe to appear at jazz festivals. In 1957, he attempted to break into the teenage rock-and-roll market with his version of Party Doll, the Buddy Knox hit. His version on Decca 30211 made No. 56 on Billboard's Pop chart and it received a UK release on Brunswick 05655.

A lifelong friend of Bing Crosby, he appears in many of Crosby's radio shows in the 1940s and 1950s. Wingy Manone lived in Las Vegas from 1954 up until his death and he stayed active until near the end, although he only recorded one full album (for Storyville in 1966) after 1960. Wingy died on July 9th 1982 in Las Vegas. Manone was largely forgotten by that time despite performing until the end. However, his talent and his ability should not be underestimated. Wingy did more musically with one arm what most people can not do with two working arms....

Friday, June 7, 2013

MOVIE REVIEW: THE CLOCK

I am not the biggest Judy Garland fan out there. I respect her supreme talent, and I enjoy her singing to a degree, but once drugs completely took over her life and her voice lost something I lost interest in her. However, in 1945 Judy was still at the top of her game - she was a big recording star at Decca Records, and she was one of the most popular stars MGM had on their lot. Garland could almost make any movie she wanted, and she did with her first dramatic effort The Clock (1945).

Garland had asked to star in a straight dramatic role after growing tired of the strenuous schedules of musical films. Although the studio was hesitant, the producer, Arthur Freed, eventually approached Garland with the script for The Clock after buying the rights to the short unpublished story by Pauline and Paul Gallico. Initially, Fred Zinnemann was brought in to direct the picture. After about a month he was removed at the request of Garland. There was a lack of chemistry between the two and early footage was disappointing.

When Freed asked who Garland wanted to direct the film, she answered, "Vincente Minnelli". Minnelli had just directed Garland the previous year in Meet Me in St. Louis, which was a tremendous success. Moreover, she and Minnelli had become romantically involved during the principal photography of Meet Me In St. Louis. During production of The Clock, they rekindled their romance, and were engaged by the end of shooting. Minnelli discarded footage shot by Zinnemann and reshaped the film. He revised some scenes, tightened up the script and incorporated New York City into the film's setting as a third character. As with Meet Me in St. Louis, he supervised adjustments to Garland's costumes, make-up and hair.

Both producer Arthur Freed and Roger Edens have a cameo in this film. Near the beginning, Freed lights Walker's cigarette and then gives him the lighter. Edens, a music arranger and close friend to Garland, plays piano in a restaurant. Screenwriter Robert Nathan appears uncredited smoking a pipe. Though the film was shot entirely on the MGM lot in Culver City, Minnelli managed to make New York City believable, even duplicating Penn Station at a reported cost of $66,000.

Both stars of The Clock were plagued by personal problems that continued throughout their lives. During filming, Garland became increasingly addicted to prescription drugs given by the studio to control her weight and pep her up. Just prior to filming the The Clock, Walker learned his wife, Jennifer Jones, was having an affair with film producer David O. Selznick and wanted a divorce. Walker began to spiral downward. During filming, Garland would often find him drunk in a Los Angeles bar and then sober him up throughout the night so he could appear before cameras the next day.

Many audiences who were surprised and disappointed to find that Garland did not sing in the film, were nevertheless impressed by her performance. It would be 16 years, however, before she would make another dramatic film, 1961's Judgment at Nuremberg, which was ashame because Garland had the acting ability to tackle drama.

Although this film, released on May 25, 1945, made a respectable profit, it was not as successful as Meet Me in St. Louis, released the previous year. Because World War II was ending, The Clock's story was not a popular choice among film-goers who wanted to put the war behind them. Nevertheless, it was well received by critics who favorably noted Garland's transformation into a mature actress. Judy Garland and Robert Walker worked well together as two people who meet while the soldier (Walker) is on leave. In a few hours Walker and Garland are in love - does that happen in real life?

Judy Garland and Robert Walker were the stars of the movie with New York City as a great co-star. Also look for great character actors like James Gleason, Keenan Wynn (he has a great appearance in a restaurant scene), and Ruth Brady among others. The Clock is a hidden gem among Garland's mammoth musical filmography. Take some time (no pun intended) and check out the movie if you like a great war story that will tug at your heart strings...

MY RATING: 9 OUT OF 10

Garland had asked to star in a straight dramatic role after growing tired of the strenuous schedules of musical films. Although the studio was hesitant, the producer, Arthur Freed, eventually approached Garland with the script for The Clock after buying the rights to the short unpublished story by Pauline and Paul Gallico. Initially, Fred Zinnemann was brought in to direct the picture. After about a month he was removed at the request of Garland. There was a lack of chemistry between the two and early footage was disappointing.

When Freed asked who Garland wanted to direct the film, she answered, "Vincente Minnelli". Minnelli had just directed Garland the previous year in Meet Me in St. Louis, which was a tremendous success. Moreover, she and Minnelli had become romantically involved during the principal photography of Meet Me In St. Louis. During production of The Clock, they rekindled their romance, and were engaged by the end of shooting. Minnelli discarded footage shot by Zinnemann and reshaped the film. He revised some scenes, tightened up the script and incorporated New York City into the film's setting as a third character. As with Meet Me in St. Louis, he supervised adjustments to Garland's costumes, make-up and hair.

Both producer Arthur Freed and Roger Edens have a cameo in this film. Near the beginning, Freed lights Walker's cigarette and then gives him the lighter. Edens, a music arranger and close friend to Garland, plays piano in a restaurant. Screenwriter Robert Nathan appears uncredited smoking a pipe. Though the film was shot entirely on the MGM lot in Culver City, Minnelli managed to make New York City believable, even duplicating Penn Station at a reported cost of $66,000.

Both stars of The Clock were plagued by personal problems that continued throughout their lives. During filming, Garland became increasingly addicted to prescription drugs given by the studio to control her weight and pep her up. Just prior to filming the The Clock, Walker learned his wife, Jennifer Jones, was having an affair with film producer David O. Selznick and wanted a divorce. Walker began to spiral downward. During filming, Garland would often find him drunk in a Los Angeles bar and then sober him up throughout the night so he could appear before cameras the next day.

Many audiences who were surprised and disappointed to find that Garland did not sing in the film, were nevertheless impressed by her performance. It would be 16 years, however, before she would make another dramatic film, 1961's Judgment at Nuremberg, which was ashame because Garland had the acting ability to tackle drama.

Although this film, released on May 25, 1945, made a respectable profit, it was not as successful as Meet Me in St. Louis, released the previous year. Because World War II was ending, The Clock's story was not a popular choice among film-goers who wanted to put the war behind them. Nevertheless, it was well received by critics who favorably noted Garland's transformation into a mature actress. Judy Garland and Robert Walker worked well together as two people who meet while the soldier (Walker) is on leave. In a few hours Walker and Garland are in love - does that happen in real life?

Judy Garland and Robert Walker were the stars of the movie with New York City as a great co-star. Also look for great character actors like James Gleason, Keenan Wynn (he has a great appearance in a restaurant scene), and Ruth Brady among others. The Clock is a hidden gem among Garland's mammoth musical filmography. Take some time (no pun intended) and check out the movie if you like a great war story that will tug at your heart strings...

MY RATING: 9 OUT OF 10

Thursday, June 6, 2013

RIP: ESTHER WILLIAMS

Her talent was more than just her swimming ability. Her beauty and her screen prescene made her a favorite of a generation of film goers. One of MGM's greatest stars - Esther Williams has died. She was 91.

Williams's died early Thursday in her sleep, according to her longtime publicist Harlan Boll.

Following in the footsteps of Sonja Henie, who went from skating champion to movie star, Williams became one of Hollywood's biggest moneymakers, appearing in spectacular swimsuit numbers that capitalized on her wholesome beauty and perfect figure. Such films as "Easy to Wed," "Neptune's Daughter" and "Dangerous When Wet" followed the same formula: romance, music, a bit of comedy and a flimsy plot that provided excuses to get Esther into the water. The extravaganzas dazzled a second generation via television and the compilation films "That's Entertainment." Williams' co-stars included the pick of the MGM contract list, including Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, Red Skelton, Ricardo Montalban and Howard Keel.

When hard times signaled the end of big studios and costly musicals in the mid-'50s, Williams tried non-swimming roles with little success. After her 1962 marriage to Fernando Lamas, her co-star in "Dangerous When Wet," she retired from public life.

She explained in a 1984 interview: "A really terrific guy comes along and says, 'I wish you'd stay home and be my wife,' and that's the most logical thing in the world for a Latin. And I loved being a Latin wife - you get treated very well. There's a lot of attention in return for that sacrifice."

She came to films after winning 100-meter freestyle and other races at the 1939 national championships and appearing at the San Francisco World's Fair's swimming exhibition.

After leaving MGM, she starred in two Universal dramatic films, "The Unguarded Moment" (excellent movie) and "Raw Wind in Eden." Neither was successful. In 1961 Lamas directed her last film, "The Magic Fountain," in Spain. It was never released in America.

Esther Jane Williams grew up destined for a career in athletics. She was born Aug. 8, 1921, in Inglewood, a suburb southwest of Los Angeles, one of five children. A public pool was not far from the modest home where Williams was raised, and it was there that an older sister taught her to swim. They saved the 10-cent admission price by counting 100 towels. When she was in her teens, the Los Angeles Athletic Club offered to train her four hours a day, aiming for the 1940 Olympic Games at Helsinki. In 1939, she won the Women's Outdoor Nationals title in the 100-meter freestyle, set a record in the 100-meter breaststroke and was a part of several winning relay teams. But the outbreak of war in Europe that year canceled the 1940 Olympics, and Esther dropped out of competition to earn a living.

Lamas was Williams' third husband. Before her fame she was married briefly to a medical student. In 1945 she wed Ben Gage, a radio announcer, and they had three children, Benjamin, Kimball and Susan. They divorced in 1958. After Lamas' death in 1982, Williams regained the spotlight. Having popularized synchronized swimming with her movies, she was co-host of the event on television at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. She issued a video teaching children how to swim and sponsored her own line of swimsuits.

"I've been a lucky lady," she said in a 1984 interview with The Associated Press. "I've had three exciting careers. Before films I had the experience of competitive swimming, with the incredible fun of winning. ... I had a movie career with all the glamor that goes with it. That was ego-fulfilling, but it was like the meringue on the pie. My marriage with Fernando - that was the filling, that was the apple in the pie."

SOURCE

Williams's died early Thursday in her sleep, according to her longtime publicist Harlan Boll.

Following in the footsteps of Sonja Henie, who went from skating champion to movie star, Williams became one of Hollywood's biggest moneymakers, appearing in spectacular swimsuit numbers that capitalized on her wholesome beauty and perfect figure. Such films as "Easy to Wed," "Neptune's Daughter" and "Dangerous When Wet" followed the same formula: romance, music, a bit of comedy and a flimsy plot that provided excuses to get Esther into the water. The extravaganzas dazzled a second generation via television and the compilation films "That's Entertainment." Williams' co-stars included the pick of the MGM contract list, including Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, Red Skelton, Ricardo Montalban and Howard Keel.

When hard times signaled the end of big studios and costly musicals in the mid-'50s, Williams tried non-swimming roles with little success. After her 1962 marriage to Fernando Lamas, her co-star in "Dangerous When Wet," she retired from public life.

She explained in a 1984 interview: "A really terrific guy comes along and says, 'I wish you'd stay home and be my wife,' and that's the most logical thing in the world for a Latin. And I loved being a Latin wife - you get treated very well. There's a lot of attention in return for that sacrifice."

She came to films after winning 100-meter freestyle and other races at the 1939 national championships and appearing at the San Francisco World's Fair's swimming exhibition.

After leaving MGM, she starred in two Universal dramatic films, "The Unguarded Moment" (excellent movie) and "Raw Wind in Eden." Neither was successful. In 1961 Lamas directed her last film, "The Magic Fountain," in Spain. It was never released in America.

Esther Jane Williams grew up destined for a career in athletics. She was born Aug. 8, 1921, in Inglewood, a suburb southwest of Los Angeles, one of five children. A public pool was not far from the modest home where Williams was raised, and it was there that an older sister taught her to swim. They saved the 10-cent admission price by counting 100 towels. When she was in her teens, the Los Angeles Athletic Club offered to train her four hours a day, aiming for the 1940 Olympic Games at Helsinki. In 1939, she won the Women's Outdoor Nationals title in the 100-meter freestyle, set a record in the 100-meter breaststroke and was a part of several winning relay teams. But the outbreak of war in Europe that year canceled the 1940 Olympics, and Esther dropped out of competition to earn a living.

Lamas was Williams' third husband. Before her fame she was married briefly to a medical student. In 1945 she wed Ben Gage, a radio announcer, and they had three children, Benjamin, Kimball and Susan. They divorced in 1958. After Lamas' death in 1982, Williams regained the spotlight. Having popularized synchronized swimming with her movies, she was co-host of the event on television at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. She issued a video teaching children how to swim and sponsored her own line of swimsuits.

"I've been a lucky lady," she said in a 1984 interview with The Associated Press. "I've had three exciting careers. Before films I had the experience of competitive swimming, with the incredible fun of winning. ... I had a movie career with all the glamor that goes with it. That was ego-fulfilling, but it was like the meringue on the pie. My marriage with Fernando - that was the filling, that was the apple in the pie."

SOURCE