By the time Lucille Ball died in 1989, her voice was a raspy mess from years of cigarette smoking. She must have gotten a life time supply of Chesterfield cigarettes from doing this print ad for them while appearing in the RKO movie Easy Living (aka Interference) in 1949...

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

Friday, September 23, 2016

HEALTHWATCH: TERRY JONES

Monty Python star Terry Jones has been diagnosed with a severe variant of dementia.

The 74-year-old is suffering from primary progressive aphasia, which affects his ability to communicate.

As a result, Jones "is no longer able to give interviews", his spokesman said.

The news was confirmed as Bafta Cymru announced the Welsh-born comedian is to be honoured with an outstanding contribution award.

The National Aphasia Association describes primary progressive aphasia as a neurological syndrome in which language capabilities become slowly and progressively impaired.

"It commonly begins as a subtle disorder of language, progressing to a nearly total inability to speak, in its most severe stage," their website states.

The 74-year-old is suffering from primary progressive aphasia, which affects his ability to communicate.

As a result, Jones "is no longer able to give interviews", his spokesman said.

The news was confirmed as Bafta Cymru announced the Welsh-born comedian is to be honoured with an outstanding contribution award.

The National Aphasia Association describes primary progressive aphasia as a neurological syndrome in which language capabilities become slowly and progressively impaired.

"It commonly begins as a subtle disorder of language, progressing to a nearly total inability to speak, in its most severe stage," their website states.

Jones, who is from Colwyn Bay in north Wales, was a member of the legendary comedy troupe with Terry Gilliam, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Michael Palin and the late Graham Chapman.

He directed Monty Python's Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life and co-directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail with Gilliam.

The surviving members reunited for 10 reunion performances at the O2 Arena in London in 2014.

Kathryn Smith, director of operations at Alzheimer's Society, said: "We are deeply sorry to hear about Terry Jones's diagnosis of dementia and are thinking of Terry and his family during this time."

He directed Monty Python's Life of Brian and The Meaning of Life and co-directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail with Gilliam.

The surviving members reunited for 10 reunion performances at the O2 Arena in London in 2014.

Kathryn Smith, director of operations at Alzheimer's Society, said: "We are deeply sorry to hear about Terry Jones's diagnosis of dementia and are thinking of Terry and his family during this time."

RIP: BOBBY BREEN

He was a big box-office attraction for RKO Radio Pictures, and his likeness appears on the album cover of the Beatles' 'Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.'

Bobby Breen, the celebrated boy soprano and child actor who appeared in a quick succession of popular 1930s films before puberty set in, has died. He was 88.

Breen died Monday of natural causes in a hospital in Pompano Beach, Fla., his daughter-in-law Jackie Howard told The Hollywood Reporter. His wife of 54 years, Audre, had died there three days earlier.

Breen's likeness is among those in the crowd pictured on the cover of the 1967 Beatles recordSgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Film historian Rhett Bartlett notes that there are only five survivors left from that memorable album cover — Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, singer-songwriter Dion and sculptor Larry Bell.

Born in Canada on Nov. 4, 1927, Breen was pushed by his older sister to become a performer. He came to Hollywood when he was about 8 and sang on Eddie Cantor's weekly radio program.

With a reputation as "a boy Shirley Temple," the curly haired, dimpled Breen made his movie debut as an opera singer in Let's Sing Again (1936) for RKO Radio Pictures.

The youngster followed with a blitz of top-billed singing roles in such films as Rainbow on the River (1936), Make a Wish (1937) — where he is befriended by a composer played by Basil Rathbone — Hawaii Calls (1938), Way Down South (1939) and Fisherman's Wharf (1939).

However, his voice naturally changed as he became a teenager, and following production of Escape to Paradise (1939), he was done with the movies after a small role in Johnny Doughboy(1942), starring Jane Withers.

"When you've been a child star and suddenly find yourself with a husky voice, it's hard to convince agents that you're not over the hill," he told the Port Charlotte Daily Herald News in a 1977 interview.

After serving in the military during World War II — he entertained the troops with Mickey Rooney — Breen performed in nightclubs, played piano in the NBC orchestra, recorded a few songs for Motown and chatted about his showbiz experiences on TV talk shows.

More recently, he and his wife booked older acts to perform in Florida retirement communities and on cruises and military bases.

Survivors also include his son Ron...

Bobby Breen, the celebrated boy soprano and child actor who appeared in a quick succession of popular 1930s films before puberty set in, has died. He was 88.

Breen died Monday of natural causes in a hospital in Pompano Beach, Fla., his daughter-in-law Jackie Howard told The Hollywood Reporter. His wife of 54 years, Audre, had died there three days earlier.

Breen's likeness is among those in the crowd pictured on the cover of the 1967 Beatles recordSgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Film historian Rhett Bartlett notes that there are only five survivors left from that memorable album cover — Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, singer-songwriter Dion and sculptor Larry Bell.

Born in Canada on Nov. 4, 1927, Breen was pushed by his older sister to become a performer. He came to Hollywood when he was about 8 and sang on Eddie Cantor's weekly radio program.

With a reputation as "a boy Shirley Temple," the curly haired, dimpled Breen made his movie debut as an opera singer in Let's Sing Again (1936) for RKO Radio Pictures.

The youngster followed with a blitz of top-billed singing roles in such films as Rainbow on the River (1936), Make a Wish (1937) — where he is befriended by a composer played by Basil Rathbone — Hawaii Calls (1938), Way Down South (1939) and Fisherman's Wharf (1939).

However, his voice naturally changed as he became a teenager, and following production of Escape to Paradise (1939), he was done with the movies after a small role in Johnny Doughboy(1942), starring Jane Withers.

"When you've been a child star and suddenly find yourself with a husky voice, it's hard to convince agents that you're not over the hill," he told the Port Charlotte Daily Herald News in a 1977 interview.

After serving in the military during World War II — he entertained the troops with Mickey Rooney — Breen performed in nightclubs, played piano in the NBC orchestra, recorded a few songs for Motown and chatted about his showbiz experiences on TV talk shows.

More recently, he and his wife booked older acts to perform in Florida retirement communities and on cruises and military bases.

Survivors also include his son Ron...

Thursday, September 22, 2016

FORGOTTEN ONES: JOAN WEBER

I guess you can consider singer Joan Weber a one-hit wonder, She burst on to the scene with the haunting song "Let Me Go Lover" but did not match that success with much else. New Jersey-born Joan Weber, fresh out of high school in 1954, had been auditioning around the New York area without catching a break. Already married and expecting a child (though her condition wasn't yet physically obvious), she was intent on a career as a professional singer.

She met up with manager Eddie Joy, who was impressed with the teenager's strong voice, and he subsequently set up a meeting with Charles Randolph Grean, a songwriter/producer (who had several years earlier written Phil Harris' hit novelty song "The Thing," Joan made a demo recording of "Marionette," a pop tune that revealed an emotionally weepy vocal approach, a bit exaggerated when compared to the other popular singers of the day. Grean, a producer and bandleader with RCA Victor, couldn't convince the label's executives to give her a shot, so he sent the demo to Mitch Miller, the head of artists and repertoire at Columbia Records.

Miller took a song entitled "Let Me Go, Devil" by Jenny Lou Carson and Al Hill and had it rewritten as "Let Me Go, Lover!" for Weber, who recorded it on the Columbia label. She recorded "Let Me Go Lover," backed by Jimmy Carroll and his orchestra, with songwriting credits going to Carson and the pseudoynm Al Hill in place of the trio of lyrics-revisers. It was released in November '54 with "Marionette" on the B side.

Mitch pulled some strings and suddenly Let Me Go Lover had become the title of an episode of Westinghouse Studio One, a long-running CBS anthology program. Broadcast on November 15, 1954, the teleplay concerned a disc jockey involved in a murder. Joan's recording of the song was featured six times during the episode in varying lengths ranging from excerpts to the entire song.

Miller, anticipating demand for the unique recording, had arranged for thousands of 45s and 78s to be shipped to record stores across the country prior to the airing. Immediately, his hunch paid off...the record began selling like crazy the very next day. To further promote the single, Joan, recently turned 19 and noticeably pregnant, made appearances on television variety shows including Ed Sullivan's Toast of the Town in December.

Mitch Miller, in a 2004 interview for the Archive of American Television, recalled that Weber's husband assumed total control of the singer's activities, thus depriving Weber of experienced career guidance. Consequently the song was her only recording to chart. Columbia dropped her after her contract was up, because she could not promote her music and be a mother at the same time.

At some point it seemed as though Joan had vanished into thin air. No one at Columbia Records had a clue as to where she was. In 1969 the company mailed a royalty check to her last known residence, but it was returned stamped "address unknown." For years her whereabouts were a mystery until she turned up in a New Jersey mental facility sometime in the 1970s. In May 1981, while still institutionalized, Joan Weber died of heart failure. She was 45 years old...

She met up with manager Eddie Joy, who was impressed with the teenager's strong voice, and he subsequently set up a meeting with Charles Randolph Grean, a songwriter/producer (who had several years earlier written Phil Harris' hit novelty song "The Thing," Joan made a demo recording of "Marionette," a pop tune that revealed an emotionally weepy vocal approach, a bit exaggerated when compared to the other popular singers of the day. Grean, a producer and bandleader with RCA Victor, couldn't convince the label's executives to give her a shot, so he sent the demo to Mitch Miller, the head of artists and repertoire at Columbia Records.

Miller took a song entitled "Let Me Go, Devil" by Jenny Lou Carson and Al Hill and had it rewritten as "Let Me Go, Lover!" for Weber, who recorded it on the Columbia label. She recorded "Let Me Go Lover," backed by Jimmy Carroll and his orchestra, with songwriting credits going to Carson and the pseudoynm Al Hill in place of the trio of lyrics-revisers. It was released in November '54 with "Marionette" on the B side.

Mitch pulled some strings and suddenly Let Me Go Lover had become the title of an episode of Westinghouse Studio One, a long-running CBS anthology program. Broadcast on November 15, 1954, the teleplay concerned a disc jockey involved in a murder. Joan's recording of the song was featured six times during the episode in varying lengths ranging from excerpts to the entire song.

Miller, anticipating demand for the unique recording, had arranged for thousands of 45s and 78s to be shipped to record stores across the country prior to the airing. Immediately, his hunch paid off...the record began selling like crazy the very next day. To further promote the single, Joan, recently turned 19 and noticeably pregnant, made appearances on television variety shows including Ed Sullivan's Toast of the Town in December.

Joan gave birth to her daughter while the record was cresting the charts. At the first opportunity, Miller got her back into the studio for a follow-up single, the Ivory Joe Hunter song "It May Sound Silly," a record survey no-show overshadowed by The McGuire Sisters' hit pop version and Hunter's R&B original. Momentum slipped away with successive efforts, varied in style and quality ("Lover-Lover," a misguided attempt at recapturing the magic of the first single, "Goodbye Lollipops, Hello Lipstick," a stab at the teen scene, and "Gone," a cover of Ferlin Husky's massive country and pop hit). By the time "Saturday Lover - Sunday Stranger" came out in the spring of 1957, it had become obvious a second hit wasn't in the cards.

After Columbia dropped her, she performed whenever possible in clubs and at minor events before abandoning what was left of her show business career.

Mitch Miller, in a 2004 interview for the Archive of American Television, recalled that Weber's husband assumed total control of the singer's activities, thus depriving Weber of experienced career guidance. Consequently the song was her only recording to chart. Columbia dropped her after her contract was up, because she could not promote her music and be a mother at the same time.

At some point it seemed as though Joan had vanished into thin air. No one at Columbia Records had a clue as to where she was. In 1969 the company mailed a royalty check to her last known residence, but it was returned stamped "address unknown." For years her whereabouts were a mystery until she turned up in a New Jersey mental facility sometime in the 1970s. In May 1981, while still institutionalized, Joan Weber died of heart failure. She was 45 years old...

Friday, September 16, 2016

PHOTOS OF THE DAY: DAN DAILEY

One of the most underrated musical stars in all of Hollywood was dancer Dan Dailey (1915-1978). He not only was a dancer but he could sing and act and do drama. Unfortunately, his life was not as happy as the movies he made. His only son commited suicide in 1975, and Dailey himself would die at the young age of 63.

Here are some pictures of Dan Dailey through the years...

Here are some pictures of Dan Dailey through the years...

|

| With Betty Grable (1916-1973) |

|

| With Cyd Charisse (1922-2008) |

Saturday, September 10, 2016

BORN ON THIS DAY: BESSIE LOVE

I have to admit I know very little about silent screen actress Bessie Love, so when I saw her birthday was coming up, I figured it would be a perfect time to do some research on her. Bessie Love was born Juanita Horton in Midland, Texas on September 10, 1898. She attended school in Midland until she was in the eighth grade, when her chiropractor father moved his family to Arizona, New Mexico, and then to Hollywood.

On actor Tom Mix's recommendation that she "get into pictures", Love's mother sent her to Biograph Studios, where she met pioneering film director D.W. Griffith. Griffith, who introduced Bessie Love to films, also gave the actress her screen name. He gave her a small role in his film Intolerance (1916). Love dropped out of Los Angeles High School to pursue her film career, although she completed her degree many years later.

Her "first role of importance" was in The Flying Torpedo; she later appeared opposite William S. Hart in The Aryan and with Douglas Fairbanks in The Good Bad Man,Reggie Mixes In, and The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (all 1916). In her early career, she was often compared to Mary Pickford, even called "Our Mary" by D.W. Griffith.

Love took an active role in the management of her career, upgrading her representation to Gerald C. Duffy, the former editor of Picture-Play Magazine, and publicizing herself by playing the ukulele and dancing for members of the military. Even glowing reviews of her films criticized the venues in which they were shown, citing this as a reason she was not a more awarded actress.

Love was able to successfully transition to talkies, and in 1929 she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for The Broadway Melody. She appeared in several other early musicals, including The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (1929), Chasing Rainbows (1930), Good News (1930), and They Learned About Women (1930).

However, by 1932, her American film career was in decline. She moved to England in 1935 and did stage work and occasional films there. Love briefly returned to the United States in 1936 to seek divorce.

During World War II in Britain, when Love found acting work hard to come by, she was the "continuity girl" on the film drama San Demetrio London (1943), an account of a ship badly damaged in the Atlantic but whose crew managed to bring her to port.

After the war, she resumed work on the stage and played small roles in films—often as an American tourist. Stage work included such productions as Love in Idleness (1944) and Born Yesterday (1947). She wrote and performed in The Homecoming, a semiautobiographical play, which had its opening in Perth, Scotland in 1958. Film work included The Barefoot Contessa (1954) with Humphrey Bogart, Ealing Studios' Nowhere to Go (1958), and The Greengage Summer (1961) starring Kenneth More. She also played small roles in the James Bond thriller On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969) and in Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971). In addition to playing the mother of Vanessa Redgrave's titular character in Isadora (1968), Love also served as dialect coach to the actress.

Her film work continued in the 1980s with roles in Ragtime (1981), Reds (1981), Lady Chatterley's Lover (1981), and—her final film—The Hunger (1983). She died in London, England from natural causes on April 26, 1986...

On actor Tom Mix's recommendation that she "get into pictures", Love's mother sent her to Biograph Studios, where she met pioneering film director D.W. Griffith. Griffith, who introduced Bessie Love to films, also gave the actress her screen name. He gave her a small role in his film Intolerance (1916). Love dropped out of Los Angeles High School to pursue her film career, although she completed her degree many years later.

Her "first role of importance" was in The Flying Torpedo; she later appeared opposite William S. Hart in The Aryan and with Douglas Fairbanks in The Good Bad Man,Reggie Mixes In, and The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (all 1916). In her early career, she was often compared to Mary Pickford, even called "Our Mary" by D.W. Griffith.

Love took an active role in the management of her career, upgrading her representation to Gerald C. Duffy, the former editor of Picture-Play Magazine, and publicizing herself by playing the ukulele and dancing for members of the military. Even glowing reviews of her films criticized the venues in which they were shown, citing this as a reason she was not a more awarded actress.

Love was able to successfully transition to talkies, and in 1929 she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for The Broadway Melody. She appeared in several other early musicals, including The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (1929), Chasing Rainbows (1930), Good News (1930), and They Learned About Women (1930).

However, by 1932, her American film career was in decline. She moved to England in 1935 and did stage work and occasional films there. Love briefly returned to the United States in 1936 to seek divorce.

During World War II in Britain, when Love found acting work hard to come by, she was the "continuity girl" on the film drama San Demetrio London (1943), an account of a ship badly damaged in the Atlantic but whose crew managed to bring her to port.

After the war, she resumed work on the stage and played small roles in films—often as an American tourist. Stage work included such productions as Love in Idleness (1944) and Born Yesterday (1947). She wrote and performed in The Homecoming, a semiautobiographical play, which had its opening in Perth, Scotland in 1958. Film work included The Barefoot Contessa (1954) with Humphrey Bogart, Ealing Studios' Nowhere to Go (1958), and The Greengage Summer (1961) starring Kenneth More. She also played small roles in the James Bond thriller On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969) and in Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971). In addition to playing the mother of Vanessa Redgrave's titular character in Isadora (1968), Love also served as dialect coach to the actress.

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

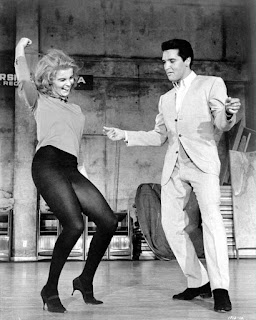

RECENTLY VIEWED: VIVA LAS VEGAS

My friend is a HUGE Elvis Presley fan. His son's middle name is even Elvis, and recently our kids had a sleepover, and I decided to pick an Elvis movie for the festivities to his delight. I picked my favorite Elvis Presley movie, Viva Las Vegas. Viva Las Vegas is a 1964 American musical film starring Elvis Presley and actress Ann-Margret. Directed by golden age Hollywood musical director George Sidney, the film is regarded by fans and by film critics as one of Presley's best movies, and it is noted for the on-screen chemistry between Presley and Ann-Margret. It also presents a strong set of ten musical song-and-dance scenes choreographed by David Winters and featured his dancers. Viva Las Vegas was a hit at movie theaters, becoming the number 14 movie in the list of the Top 20 Movie Box Office hits of 1964.Based on the Box Office Report database. The movie was #14 on the Variety year end box office list of the top-grossing movies of 1964.

The plot is simple enough. Lucky Jackson (Elvis) goes to Las Vegas, Nevada to participate in the city's first annual Grand Prix Race. However, his race car, an Elva Mk. VI, is in need of a new motor (engine) in order to compete in the event. Lucky raises the necessary money in Las Vegas, but he loses it when he is shoved into the pool by the hotel's nubile swimming instructor, Rusty Martin (Ann-Margret). Lucky then has to work as a waiter at the hotel to replace the lost money to pay his hotel bill, as well as enter the hotel's talent contest in hopes of winning a cash prize sizable enough to pay for his car's engine. During all this time, Lucky attempts to win the affections of Rusty. His main competition arrives in the form of Count Elmo Mancini (Cesare Danova), who attempts to win both the Grand Prix and the affections of Rusty. Rusty soon falls in love with Lucky, and immediately tries to change him into what she wants.

In Great Britain, both the movie and its soundtrack were sold as Love In Las Vegas, since there was another, different movie called Viva Las Vegas that was being shown in British cinemas at the same time that Presley's was released.

The chemistry between the two stars was quite real during the filming of Viva Las Vegas. Presley and Ann-Margret began an affair, and this received considerable attention from movie and music gossip columnists. This reportedly led to a showdown with Presley's worried girlfriend Priscilla Beaulieu. (Elvis and Priscilla married in 1967.) In her 1985 book Elvis and Me, Priscilla Presley describes the difficulties that she experienced when the gossip columnists erroneously "announced" that Ann-Margret and Presley had become engaged to be married.

In her memoirs, Ann-Margret refers to Elvis Presley as her "soulmate" and stated: "We felt there was a need in 'The Industry' for a female Elvis Presley."

In addition, the filming of Viva Las Vegas reportedly produced unusually heated exchanges between the director, film veteran George Sidney, and Presley's manager, Colonel Tom Parker, who was not credited as a "Technical Advisor" in the film's credits.

The arguments reportedly concerned the amount of time and effort allotted by the cinematographer, Joseph Biroc, to the song and dance numbers that featured Ann-Margret, ostensibly on the orders of the director. These scenes in Viva Las Vegas include views of Ann-Margret's dancing taken from many different camera angles, the use of multiple movie cameras for each scene, and several retakes of each of her song-and-dance scenes. Despite the arguments behind the scenes, the film marked the high point of Elvis' film career, and even the kids at the sleepover got into the movie and liked it...

The plot is simple enough. Lucky Jackson (Elvis) goes to Las Vegas, Nevada to participate in the city's first annual Grand Prix Race. However, his race car, an Elva Mk. VI, is in need of a new motor (engine) in order to compete in the event. Lucky raises the necessary money in Las Vegas, but he loses it when he is shoved into the pool by the hotel's nubile swimming instructor, Rusty Martin (Ann-Margret). Lucky then has to work as a waiter at the hotel to replace the lost money to pay his hotel bill, as well as enter the hotel's talent contest in hopes of winning a cash prize sizable enough to pay for his car's engine. During all this time, Lucky attempts to win the affections of Rusty. His main competition arrives in the form of Count Elmo Mancini (Cesare Danova), who attempts to win both the Grand Prix and the affections of Rusty. Rusty soon falls in love with Lucky, and immediately tries to change him into what she wants.

In Great Britain, both the movie and its soundtrack were sold as Love In Las Vegas, since there was another, different movie called Viva Las Vegas that was being shown in British cinemas at the same time that Presley's was released.

The chemistry between the two stars was quite real during the filming of Viva Las Vegas. Presley and Ann-Margret began an affair, and this received considerable attention from movie and music gossip columnists. This reportedly led to a showdown with Presley's worried girlfriend Priscilla Beaulieu. (Elvis and Priscilla married in 1967.) In her 1985 book Elvis and Me, Priscilla Presley describes the difficulties that she experienced when the gossip columnists erroneously "announced" that Ann-Margret and Presley had become engaged to be married.

In her memoirs, Ann-Margret refers to Elvis Presley as her "soulmate" and stated: "We felt there was a need in 'The Industry' for a female Elvis Presley."

In addition, the filming of Viva Las Vegas reportedly produced unusually heated exchanges between the director, film veteran George Sidney, and Presley's manager, Colonel Tom Parker, who was not credited as a "Technical Advisor" in the film's credits.

The arguments reportedly concerned the amount of time and effort allotted by the cinematographer, Joseph Biroc, to the song and dance numbers that featured Ann-Margret, ostensibly on the orders of the director. These scenes in Viva Las Vegas include views of Ann-Margret's dancing taken from many different camera angles, the use of multiple movie cameras for each scene, and several retakes of each of her song-and-dance scenes. Despite the arguments behind the scenes, the film marked the high point of Elvis' film career, and even the kids at the sleepover got into the movie and liked it...

MY RATING: 10 OUT OF 10

Friday, September 2, 2016

THE TRAGEDY OF RUSS COLUMBO: 82 YEARS LATER

In the 1930s, Bing Crosby was considered the "king" of the crooners and rightfully so. There did not seem to be much competition to unseat Bing in those years. Bing had replaced matinee idol but nasally singer Rudy Vallee as the most popular singer in America. If I had to pick a singer that could have possibly rivaled Bing was Russ Coulmbo. Unfortunately, his life was cut short 82 years ago.

While Columbo's fledging movie career temporarily stalled, new opportunities arose in other venues. He was offered a new NBC prime-time radio series early in 1934. Emanating "deep in the heart of Hollywood," in the words of presenter Cecil Underwood, the program aired every Sunday night. Introduced as "the Romeo of songs, here with songs to delight your ears and heart," Columbo would open with the greeting "Good evening, my friends," followed by his theme, "You Call It Madness," which would also return as his closing number. His song selection featured a blend of hit recordings and plugs for material from current films, including "With My Eyes Wide Open I’m Dreaming" from Shoot the Works, "I’ve Had My Moments" from Hollywood Party, and "Rolling In Love" from The Old Fashioned Way.

At the same time, Columbo signed a new recording contract with Brunswick (once again filling the void left by the departure of Crosby to another label, in this case, Decca). Despite the absence of precise sales figures, his releases from that period reputedly sold exceedingly well. According to Robert Deal, he was reportedly earning more than $500,000 a year from all sources—a vast sum at the time.

These developments appear to have spurred Universal Pictures to select him for a major part (as Gaylord Ravenal) in the heavily-publicized film version of the Kern-Hammerstein musical, Showboat. When that project was temporarily put on hold due to production problems, Columbo was assigned an interim lead in Wake Up and Dream, a low-budget, standard backstage musical also starring June Knight, Wini Shaw, and Roger Pryor.

Public interest in Columbo was further hyped by his romance with actress Carole Lombard. In the fall of 1933, a short time after her divorce from actor William Powell, Lombard fell in love with the singer. For his part, Columbo responded favorably to her zany behavior as well as accepting her salty language, something which had offended a number of her male friends in the past. Although marriage seemed a distinct possibility, Lombard’s close associates doubted that the affair would come to that. According to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, "the couple’s relationship was based on many things – but not sex." Hopper cited a number of traits which caused her question Columbo’s masculinity, including the considerable trouble he spent on his hair and sun-tanning treatments as well as his habit of carrying around a pocket-mirror produced on occasion to gaze at himself in public. It is indisputable, however, that Lombard was devoted to him and made every effort to help further his film career. She invited Columbo onto film sets to observe the filmmaking process and to pick up pointers on acting. He repaid this favor by coaching her in the two songs she was designated to sing in the movie White Woman.

By September 1934 it was clear that Crosby’s career had thus far been more successful than his own. Columbo had appeared in only four films during 1933-1934, two of which he did not star in. Crosby on the other hand had starred in six features during the same time span. Furthermore, the material he had been given to sing in films trailed far behind that provided Crosby with regard to both quality and sheer quantity. While Crosby’s film music played a significant role in propelling him to stardom, Columbo’s song hits were for-the-most-part limited to recordings and radio broadcasts. Deal states "he had the greater romantic appeal but very little chance to demonstrate any versatility and it seems likely that there were more sides of him to be seen on film than his presenters had up to that time revealed to the cinema audiences."

Columbo and Lombard continued to date up to his death; they could be seen dining and dancing at the Cocoanut Grove most Wednesday nights. His last recording session took place on August 31, 1934; he concluded with the Allie Wrubel and Mort Dixon composition, "I See Two Lovers."

On September 2, just hours before his regular Sunday evening radio program, Columbo stopped by to see his life-long friend, Lansing V. Brown, Jr., who lived with his parents at 584 Lillian Way in Beverly Hills. He was going to have some publicity shots taken by Brown, who was highly respected as still camera man and much in demand as a portrait photographer. After the photos has been taken, they talked about a common interest, antique pistol collecting. Brown then produced a pair of duelling pistols which dated from the Civil War, part of his own collection of curios. He placed the head of a match under the rusty hammer of one of the pistols with a flourish, then pulled the trigger to ignite the match in order to light a cigarette. The pistol, which evidently hadn’t been used for over sixty-five years, still housed a charge of powder and an old bullet. The chick of the hammer caused the charge to explode and the corroded bullet struck the top of a table located between the two friends, ricocheted, striking Columbo in the left eye, then entering his brain.

Rushed to the Good Samaritan Hospital, it was discovered that the bullet, after piercing the center of the brain, had fractured the rear wall of the skull. A brain specialist summoned to the scene, Dr. George Paterson, counseled against the delicate operation being considered unless Columbo’s rapidly waning strength could be restored. The singer lingered in agony for six hours before dying; the doctors were amazed that he hadn’t been killed instantly. Bedside mourners included members of his family and former girlfriend, Sally Blane. Those outside in the hospital corridor included Lombard, who had heard of the tragedy by telephone at Lake Arrowhead where Columbo was to have joined her to vacation the following week, film producer Carl Laemmle, and other film celebrities.

A crowd of 3000 persons attended funeral services at the Sunset Boulevard Catholic Church in Hollywood. The pallbearers were Bing Crosby, Gilbert Roland, Walter Lang, Stuart Peters, Lowell Sherman, and Sheldon Keate Callaway.

Columbo’s seven surviving brothers and sisters conspired to keep news about the death from their mother. Having suffered a heart attack two days prior to Columbo’s accident, they were concerned that the shock of hearing about his death would kill her. A story was concocted about Columbo agreeing to a five-year tour abroad. While money from his life insurance policy was used to support her, the deception was maintained for a decade until she died. The family employed a variety of strategems during this period including sending letters, allegedly written by the singer, which contained newsy accounts, tender sentiments, and reports of his many successes. Warren Hall noted, in the October 8, 1944 issue of The American Weekly (a Sunday supplement distributed in the Hearst syndicated newspapers), that they took the further precaution of imprinting each envelope with a rubber stamp to simulate a London postmark. The same stamp was conspicuous on the wrappings of the Christmas and birthday gifts which arrived "from your loving son."

The family also played records in order to simulate his radio program. The only radio shows actually heard in the Columbo household were those that made no mention of bandleaders. Even though his mother was almost totally blind, all newspapers coming into the house were carefully censored. Lombard assisted by corresponding with Mrs. Columbo, explaining that her son was unable to visit because he was performing in the major cities of Europe. All visitors were warned to speak as though Russ were still alive and more popular than ever. According to Hall, when Mrs. Columbo died in 1944 at the age of 78, her last words were: "Tell Russ…I am so proud…and happy."

Many music historians have openly questioned whether the "Battle of the Baritones" would have turned out differently if Columbo’s life hadn’t been tragically ended...

While Columbo's fledging movie career temporarily stalled, new opportunities arose in other venues. He was offered a new NBC prime-time radio series early in 1934. Emanating "deep in the heart of Hollywood," in the words of presenter Cecil Underwood, the program aired every Sunday night. Introduced as "the Romeo of songs, here with songs to delight your ears and heart," Columbo would open with the greeting "Good evening, my friends," followed by his theme, "You Call It Madness," which would also return as his closing number. His song selection featured a blend of hit recordings and plugs for material from current films, including "With My Eyes Wide Open I’m Dreaming" from Shoot the Works, "I’ve Had My Moments" from Hollywood Party, and "Rolling In Love" from The Old Fashioned Way.

At the same time, Columbo signed a new recording contract with Brunswick (once again filling the void left by the departure of Crosby to another label, in this case, Decca). Despite the absence of precise sales figures, his releases from that period reputedly sold exceedingly well. According to Robert Deal, he was reportedly earning more than $500,000 a year from all sources—a vast sum at the time.

These developments appear to have spurred Universal Pictures to select him for a major part (as Gaylord Ravenal) in the heavily-publicized film version of the Kern-Hammerstein musical, Showboat. When that project was temporarily put on hold due to production problems, Columbo was assigned an interim lead in Wake Up and Dream, a low-budget, standard backstage musical also starring June Knight, Wini Shaw, and Roger Pryor.

Public interest in Columbo was further hyped by his romance with actress Carole Lombard. In the fall of 1933, a short time after her divorce from actor William Powell, Lombard fell in love with the singer. For his part, Columbo responded favorably to her zany behavior as well as accepting her salty language, something which had offended a number of her male friends in the past. Although marriage seemed a distinct possibility, Lombard’s close associates doubted that the affair would come to that. According to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, "the couple’s relationship was based on many things – but not sex." Hopper cited a number of traits which caused her question Columbo’s masculinity, including the considerable trouble he spent on his hair and sun-tanning treatments as well as his habit of carrying around a pocket-mirror produced on occasion to gaze at himself in public. It is indisputable, however, that Lombard was devoted to him and made every effort to help further his film career. She invited Columbo onto film sets to observe the filmmaking process and to pick up pointers on acting. He repaid this favor by coaching her in the two songs she was designated to sing in the movie White Woman.

By September 1934 it was clear that Crosby’s career had thus far been more successful than his own. Columbo had appeared in only four films during 1933-1934, two of which he did not star in. Crosby on the other hand had starred in six features during the same time span. Furthermore, the material he had been given to sing in films trailed far behind that provided Crosby with regard to both quality and sheer quantity. While Crosby’s film music played a significant role in propelling him to stardom, Columbo’s song hits were for-the-most-part limited to recordings and radio broadcasts. Deal states "he had the greater romantic appeal but very little chance to demonstrate any versatility and it seems likely that there were more sides of him to be seen on film than his presenters had up to that time revealed to the cinema audiences."

Columbo and Lombard continued to date up to his death; they could be seen dining and dancing at the Cocoanut Grove most Wednesday nights. His last recording session took place on August 31, 1934; he concluded with the Allie Wrubel and Mort Dixon composition, "I See Two Lovers."

On September 2, just hours before his regular Sunday evening radio program, Columbo stopped by to see his life-long friend, Lansing V. Brown, Jr., who lived with his parents at 584 Lillian Way in Beverly Hills. He was going to have some publicity shots taken by Brown, who was highly respected as still camera man and much in demand as a portrait photographer. After the photos has been taken, they talked about a common interest, antique pistol collecting. Brown then produced a pair of duelling pistols which dated from the Civil War, part of his own collection of curios. He placed the head of a match under the rusty hammer of one of the pistols with a flourish, then pulled the trigger to ignite the match in order to light a cigarette. The pistol, which evidently hadn’t been used for over sixty-five years, still housed a charge of powder and an old bullet. The chick of the hammer caused the charge to explode and the corroded bullet struck the top of a table located between the two friends, ricocheted, striking Columbo in the left eye, then entering his brain.

Rushed to the Good Samaritan Hospital, it was discovered that the bullet, after piercing the center of the brain, had fractured the rear wall of the skull. A brain specialist summoned to the scene, Dr. George Paterson, counseled against the delicate operation being considered unless Columbo’s rapidly waning strength could be restored. The singer lingered in agony for six hours before dying; the doctors were amazed that he hadn’t been killed instantly. Bedside mourners included members of his family and former girlfriend, Sally Blane. Those outside in the hospital corridor included Lombard, who had heard of the tragedy by telephone at Lake Arrowhead where Columbo was to have joined her to vacation the following week, film producer Carl Laemmle, and other film celebrities.

A crowd of 3000 persons attended funeral services at the Sunset Boulevard Catholic Church in Hollywood. The pallbearers were Bing Crosby, Gilbert Roland, Walter Lang, Stuart Peters, Lowell Sherman, and Sheldon Keate Callaway.

Columbo’s seven surviving brothers and sisters conspired to keep news about the death from their mother. Having suffered a heart attack two days prior to Columbo’s accident, they were concerned that the shock of hearing about his death would kill her. A story was concocted about Columbo agreeing to a five-year tour abroad. While money from his life insurance policy was used to support her, the deception was maintained for a decade until she died. The family employed a variety of strategems during this period including sending letters, allegedly written by the singer, which contained newsy accounts, tender sentiments, and reports of his many successes. Warren Hall noted, in the October 8, 1944 issue of The American Weekly (a Sunday supplement distributed in the Hearst syndicated newspapers), that they took the further precaution of imprinting each envelope with a rubber stamp to simulate a London postmark. The same stamp was conspicuous on the wrappings of the Christmas and birthday gifts which arrived "from your loving son."

The family also played records in order to simulate his radio program. The only radio shows actually heard in the Columbo household were those that made no mention of bandleaders. Even though his mother was almost totally blind, all newspapers coming into the house were carefully censored. Lombard assisted by corresponding with Mrs. Columbo, explaining that her son was unable to visit because he was performing in the major cities of Europe. All visitors were warned to speak as though Russ were still alive and more popular than ever. According to Hall, when Mrs. Columbo died in 1944 at the age of 78, her last words were: "Tell Russ…I am so proud…and happy."

Many music historians have openly questioned whether the "Battle of the Baritones" would have turned out differently if Columbo’s life hadn’t been tragically ended...